This article includes explicit images from a sex-education book for teenagers.

My local library is quiet during the summer weekdays. It’s small, even though it’s meant to service the 50,000 or so residents in my neighborhood in New Jersey. It’s about two blocks from where I live, so I visit frequently to give my kids a place to safely explore and eye all of the colorful décor and illustrated books. The librarians have made a ritual of coming out from behind their desk to make faces and entertain my 2-year-old son and 8-month-old daughter, who they’ve dubbed their unofficial mascot.

During one visit, as my son sat quietly messing with a loose pack of Legos, I asked a librarian if she could help me find a book. The request caught her off guard.

“Do you have It’s Perfectly Normal, by Robie H. Harris?” I asked. The librarian checked her computer. Her eyes widened when she recognized the cover. “Do we have this book?” she asked another librarian. She joined her at the terminal. “What is it? A sex-ed book for kids?” she asked. “I’ve seen this one before. It’s like, really, really detailed,” she answered with a nervous smile. “Like, very graphic.”

The senior librarian took a closer look. “Is this one of the ones that’s being banned?” she asked. “Yeah. That’s pretty much exactly why I wanted to check it out,” I told her. “Well, there’s two copies available at this other branch. We can order it and place it on hold for you.”

But I wouldn’t get my hands on Newark’s copy of It’s Perfectly Normal. When I returned a week later to pick it up, the librarian told me the copies listed as available had vanished. They weren’t checked out, but they weren’t on the shelves, either. Instead, one of the librarians offered to check out the book herself from her own local library and lend it to me.

I was eager to finally flip through it myself. I’d been fascinated by this book ever since it became the center of the right-wing push to censor books with sexual themes in the name of protecting the innocence of children. I found it funny and ironic that library books could terrify parents more than the actual dangers lurking on their smart devices.

There is no shortage of books being used to panic parents into protesting their local schools or libraries. Concerns over books like The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson are easy to shrug off, given how challengers contort themselves to argue that scenes involving sex are simultaneously promoting promiscuity. And it’s hard to believe that a child would accidentally stumble on certain hand-picked selections from novels that are hundreds of pages long.

It’s Perfectly Normal is harder to shrug away. It’s not difficult to see why this book has been an effective cudgel, both in recent years and practically since it was published: Its images are particularly blunt and graphic. That articles and social media posts about parents’ concerns over those cartoons have often blurred them out serves to prove their point. Earlier this year, a pastor in Asheville, North Carolina, made headlines after his mic was cut off during a school board meeting. “If you don’t want to hear it in a school board meeting, why should children be able to check it out of the school system?” he reportedly shouted. In an interview with an eager Fox News host, that same pastor described It’s Perfectly Normal as “hardcore porn.” On the cover, it says it’s intended for ages 10 and up, a point noted over and over again by rage-baiters wanting to frame the book as nefarious, somehow “grooming” children. Ron DeSantis, the Florida governor and presidential candidate, cited it as justification for his controversial Parental Rights in Education Act.

I felt sure that as a 34-year-old father of two there would be nothing in there that would offend my sensibilities. I’d heard nothing but glowing reviews from sex-ed pros about the child-friendly language in the book. But flipping through the book’s pages finally, I was a little shocked. I had an involuntary reaction to seeing the nude cartoons, like I needed to make sure I was alone and hide the book. I skimmed ahead to look at the rest of the book briskly. On virtually every page I stopped to examine, I was confronted with detailed drawings of genitals. It felt like every page had a cartoon of a naked body.

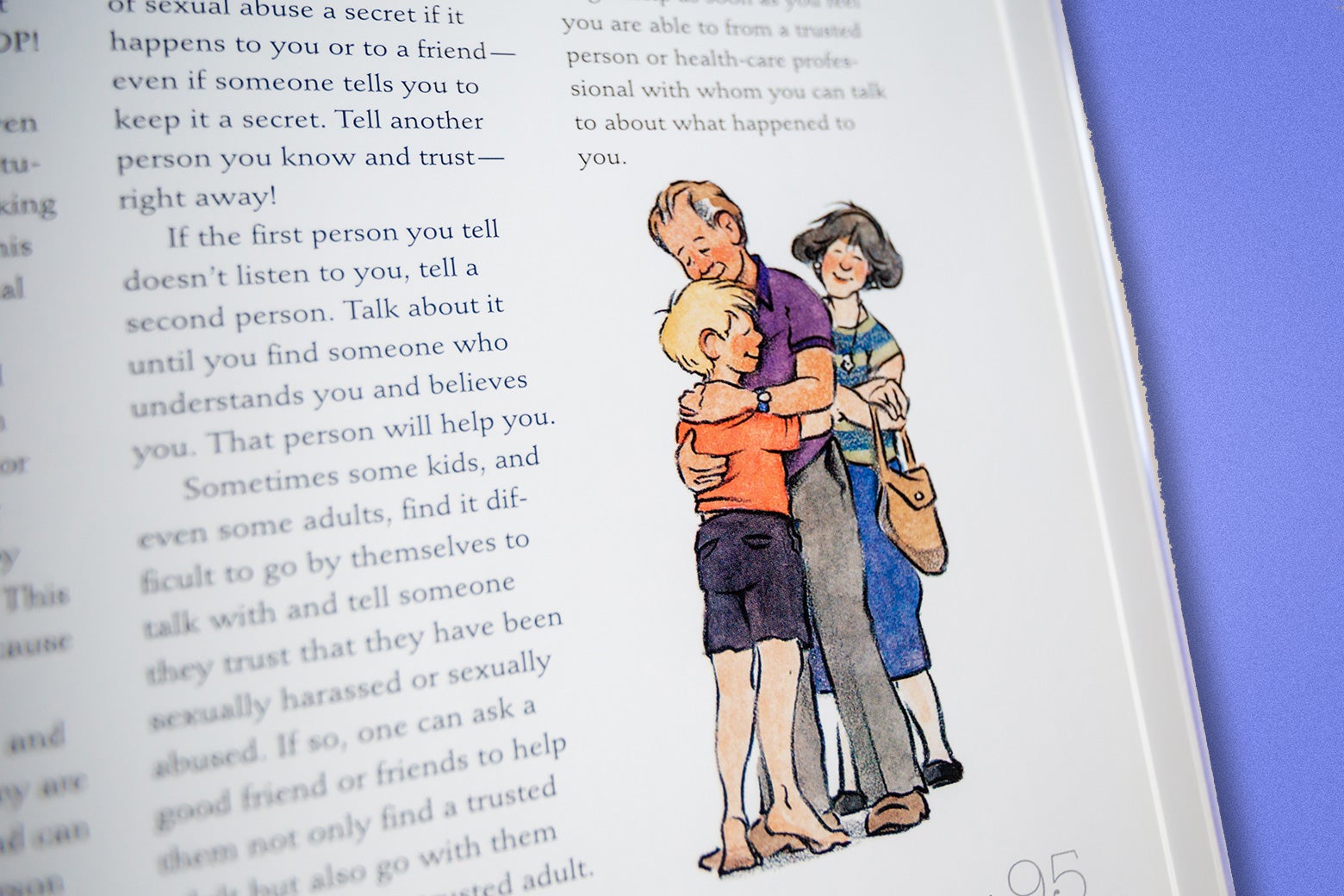

I turned back to the first page, and told myself I’d try and read it straightforwardly. At the beginning, there is a 16-panel comic strip cartoon in which two characters, a bird and a bee, agree to explore a book about sex together. These characters line the margins of the remainder of the book, as comic relief for the kids reading the book, to make the subject more approachable and less intimidating. By the time I got to Part 1, “What is Sex?” I felt my guard come down a little bit. There were comic illustrations of two babies showing their different genitals. The text invites the reader to ask questions about sex to someone they know and trust, and to remember “there are no stupid questions.” And then it explains in detail about the differences between sex and gender.

The next few sections follow much of the same pattern, exploring questions and common misconceptions about how babies are made and sexual desire. “Having crushes is perfectly normal. Not having crushes is also perfectly normal,” the book reads.

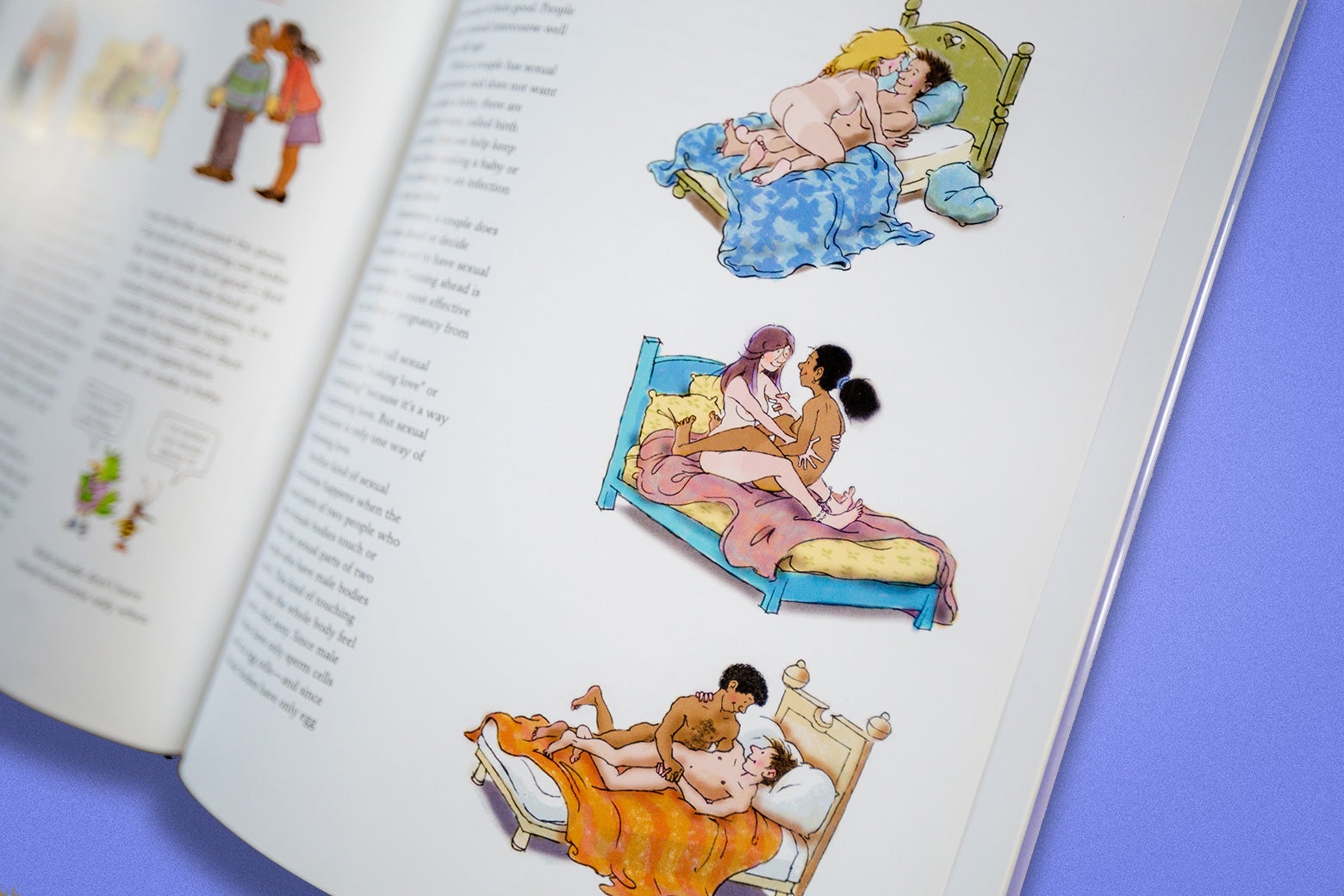

On Page 9, I came across the first illustration I recognized from the controversy. In the chapter “Making Love,” there are three graphic images that show adult bodies having sex. There is no visible penetration, but it’s still eye-popping. I was sure I wouldn’t hand this book to my kids when they are 10. And I began to wonder if in my own allergy to the book-burning fervor, I had been a little too dismissive of the parents at the root of this fight.

The American Library Association began collecting data on book bans more than 20 years ago. Last year was its most severe on record, with 2,571 unique titles challenged, up 38 percent from a year before. Many of the titles, including It’s Perfectly Normal, depict LGBTQ+ relationships and sex.

I’ve watched how this happens myself in real time. As part of my reporting on book bans, I monitored one Facebook group for moms in Arkansas. It was originally set up by local parents as a means to stay in touch after a chaotic library board meeting left parents feeling ignored. But it’s since grown exponentially into a forum into which Christian conservatives living as far away as Maine pump information about how local institutions are corrupting kids. Members from outside of Arkansas share their own guides for discovering problematic books, like this one that uses a teacher-generated guide for promoting diversity and inclusion as a baseline. The users share strategies on how to contest material anywhere, how to fill out Freedom of Information Act requests, and instructions on which specific books to challenge. This document originating in Utah lists over 100 books, and encourages anyone to try to have them pulled everywhere, not just locally.

I’ve talked to some of these moms—and on Facebook, it is usually moms—and they’ve denied that the threat from these books is theoretical or engineered. “I’ve heard stories,” one told me. “I do have one friend who said she has a son who is 12. They use the library weekly, and one of the librarians said, ‘Oh, you like that graphic novel? Let me show you. You’re really going to like these.’ And she starts pulling others out that have homosexual themes or characters. A lot of Pride stuff. And she’s like, “Wait, why are you putting this stuff into my kid’s hands?’ ”

“We come here for dinosaurs and trains and everything else, but I just can’t believe that many children are coming there wanting to find a place to talk about their sexuality,” she added.

Some of these same women described to me how they’ve become disillusioned with these groups as they became inundated with garden-variety homophobic memes, like one about Pete Buttigieg, becoming what felt like conservative-action hubs. They felt the focus was getting away from the books. It had seemed obvious to me that these parents were pawns in a politically opportunistic panic that sought to sweep Republicans into office. The content of the books was, by and large, beside the point.

It’s Perfectly Normal, more than any other frequently banned title I have flipped through, challenged my view. The images are not “pornographic,” and it’s obvious that anti-gay sentiment is partly fueling the objection to the book. But the images are graphic, and it’s startling to me to think they’re intended for kids who aren’t even in middle school yet. I realize my kids will be able to see worse on the internet before I know it, but I still wondered: Is it so crazy not to want them to be able to find this in the library?

When I called sex educator Melissa Pintor Carnagey, she told me she gets it. “I didn’t grow up with a sex-positive upbringing. I’m Puerto Rican, I’m Black, I’m Mexican, I grew up with Catholicism,” she said. “It’s been a big unlearning and relearning, raising my kids in a different way and then seeing the results of that.”

Carnagey founded Sex Positive Families, a robust online list of books and resources for sex education for parents and teachers organized by age, topic, and type. She used It’s Perfectly Normal to connect with her daughter at a young age. She confessed that when she first opened the book, she too was a little shocked, but she also wishes more parents would embrace that feeling.

“I think it’s super awesome and brave and self-aware to just name that, you know: ‘That makes me feel uncomfortable.’ And to then spend some time to ask, ‘Well, why might that be?’ ” she said. She suggested trying to think through what I wanted when it came time to talk to my kids about sex: “I had a very clear why in my approach to parenting. I wanted my daughter to know her body. I wanted her to feel that she had agency and autonomy and a sense of ownership around her own body. I didn’t want her to feel shame. I wanted her to understand her rights to pleasure, certainly before she desired to welcome anyone else to engage with her body.”

When she had a son, who is now 13, Carnagey also used It’s Perfectly Normal to teach him at a young age about all kinds of bodies. “It’s helping him to be a more empathetic person, who knows more about menstruation and periods than I knew when I was his age,” she said. “I’ve seen what good can be done by being open and meeting them where they’re at with their curiosities that evolve over time.”

I read her some of the reviews I’ve seen about this book in forums for parents that support the national push to ban books like this one:

“Seventy-eight. That’s correct—78. I didn’t even count the random, naked body *parts*. Just the naked bodies, showing genitalia.”

“I was able to teach my children about sex without this filth.”

“If that isn’t pornography, I don’t know what it is.”

Carnagey was, to my surprise, empathetic. “There’s so much more visibility and language nowadays for diverse sexuality and gender identities that our young people are very much aware of, and that can feel intimidating to adults today who didn’t grow up with that kind of language or that level of openness around identities,” she said. “That’s understandable. I just have yet to consistently see what many of these opponents’ alternatives are. If it’s silence, if it’s avoidance, shame, I absolutely do not feel that that is in the best interest of young people or of our society as a whole.”

OK—but is it absolutely necessary to show kids these graphic illustrations of sex and masturbation? My kids are very young, but even for when they’re a little older, I told Carnagey the truth about my reaction. “This is a book for education, not for entertainment,” she said. “This is normal for young people to explore their bodies, and to have representation in an educational book.”

“Those are our triggers. We weren’t born with them. They were taught to us. It says nothing about our child and their experience getting to know their body,” she said.

On Pages 20 and 21 of It’s Perfectly Normal, I came across another familiar set of illustrations. It portrayed 20 different bodies of all types, sizes, and ages, all completely naked. The bird and bee illustrations are also expressing some discomfort. “Let’s just forget we ever had this conversation. Okay?” the bee says to the bird. I’d hoped that I’d have lost all of my discomfort in looking at these naked cartoons by now, but truthfully, I still felt like I shouldn’t be looking at them—to say nothing of my kids.

Even before it was published, Robie Harris, the author, acknowledged that she knew the book would test the limits of acceptable content for a sex-education text. It was conceived in the height of the HIV crisis, and Harris, then already a veteran children’s author, reeled when a publisher first approached her about drafting a book to help kids understand HIV and AIDS. She thought any book like that would need to encompass all of sexuality. She and her illustrator spoke with dozens of sex-ed experts for their book. “I was warned by several people not to do this book, that it would ruin my career,” Harris recalled in an NPR interview during the last book-banning cycle. “But I really didn’t care. To me, it wasn’t controversial. It’s what every child has a right to know.”

People were right to worry. The title has been a regular chart-topper of the American Library Association’s list of most challenged books since 2005, way before groups like Moms For Liberty came around. Fast-forward to today, and states like Georgia, Texas, and even New Jersey have used It’s Perfectly Normal to justify challenging sex-ed books, even if the book was never used as part of their schools’ curriculums.

By now, both Harris and illustrator Michael Emberley have gotten used to defending their work. “What we are doing is not pornography. Pornography is fantasy. There is no intention in pornography to educate,” Emberley has said in defense of his illustrations. “It’s not exactly like we are reinventing this topic. Reproductive biology is science. We didn’t have to make anything up.” (Their publisher told me they couldn’t be reached to speak with me.)

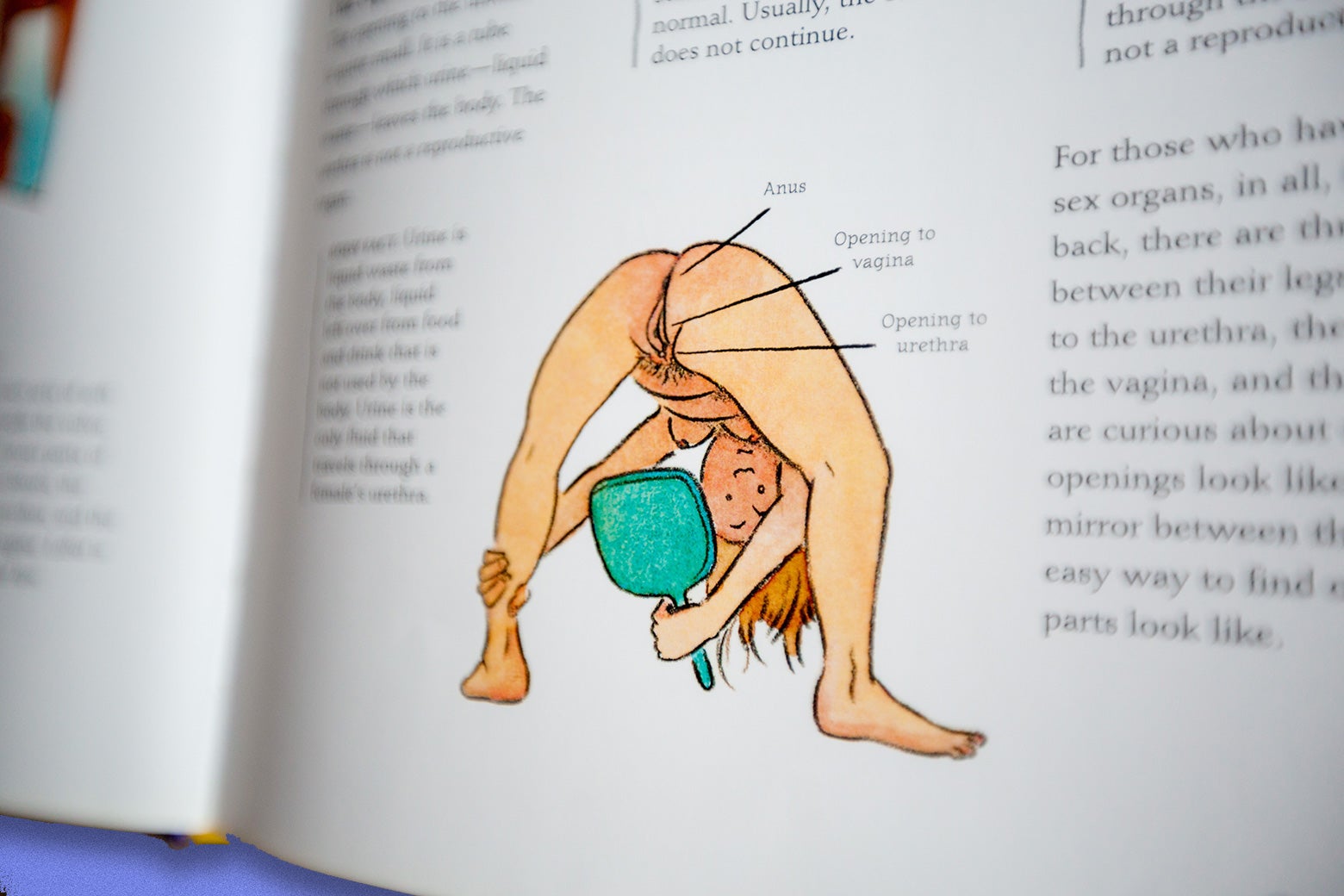

That is true, I think. But then you turn to a page of a teenage girl bending all the way over and holding a mirror between her legs to inspect her genitals. And to another page that shows both an adolescent boy and girl masturbating alongside how-to instructions. In navigating this book, I struggled to identify which illustrations felt necessary, and which felt gratuitous and inflammatory to parents who might be even more prudish and queasy than I am.

Carnagey advised that confidence is key. “There’s nothing wrong or bad with you as an adult or parent if this feels uncomfortable. You learned that. We can unlearn. It takes time, knowledge, education. And banning books that help us on that path is not the answer,” she said in a comforting tone. “How we model for them our own comfort levels around these topics ultimately helps them to do the same, to feel that confidence, and it’s lifesaving. It truly is.”

Besides, as Carnagey reminded me, what all these parents (me included) are chasing is a very illusory sense of control. “To raise children, we’re going to continually be confronted with things that we can’t control,” she said, laughing. “My daughter, when she was younger, I didn’t want to introduce sweets. But her grandmother did. And that frustrated the heck out of me. I’m trying to do X, Y and Z. Right? You learn very quickly into parenting that you actually don’t have a lot of control. So, you can decide to either stay there in your mother-anger, or you can find a way to reality, which is to acknowledge you have no control over it. So, instead, you say, ‘What do I actually have influence over?’ ”

Carnagey told me she keeps a copy of It’s Perfectly Normal in her home library, and assured me that her young boys aren’t sneaking around to peek at it. As I got further into the book, I began to see it the way Carnagey does, as a meaningful book intent on destigmatizing everything from puberty to sex, birth, and STDs. And by the end, when I got to the new section about the internet that was added when the book was rereleased for its fourth edition, I found a lot of things that I wished I had known when I was young and exploring the internet myself. So much of the information in this book would have made a huge difference.

“It’s not fair for young people to be put in the position that so many of us were in,” Carnagey told me. I don’t know if my kids are ever going to find a copy of It’s Perfectly Normal on their bookshelves, but that much I believe is true.