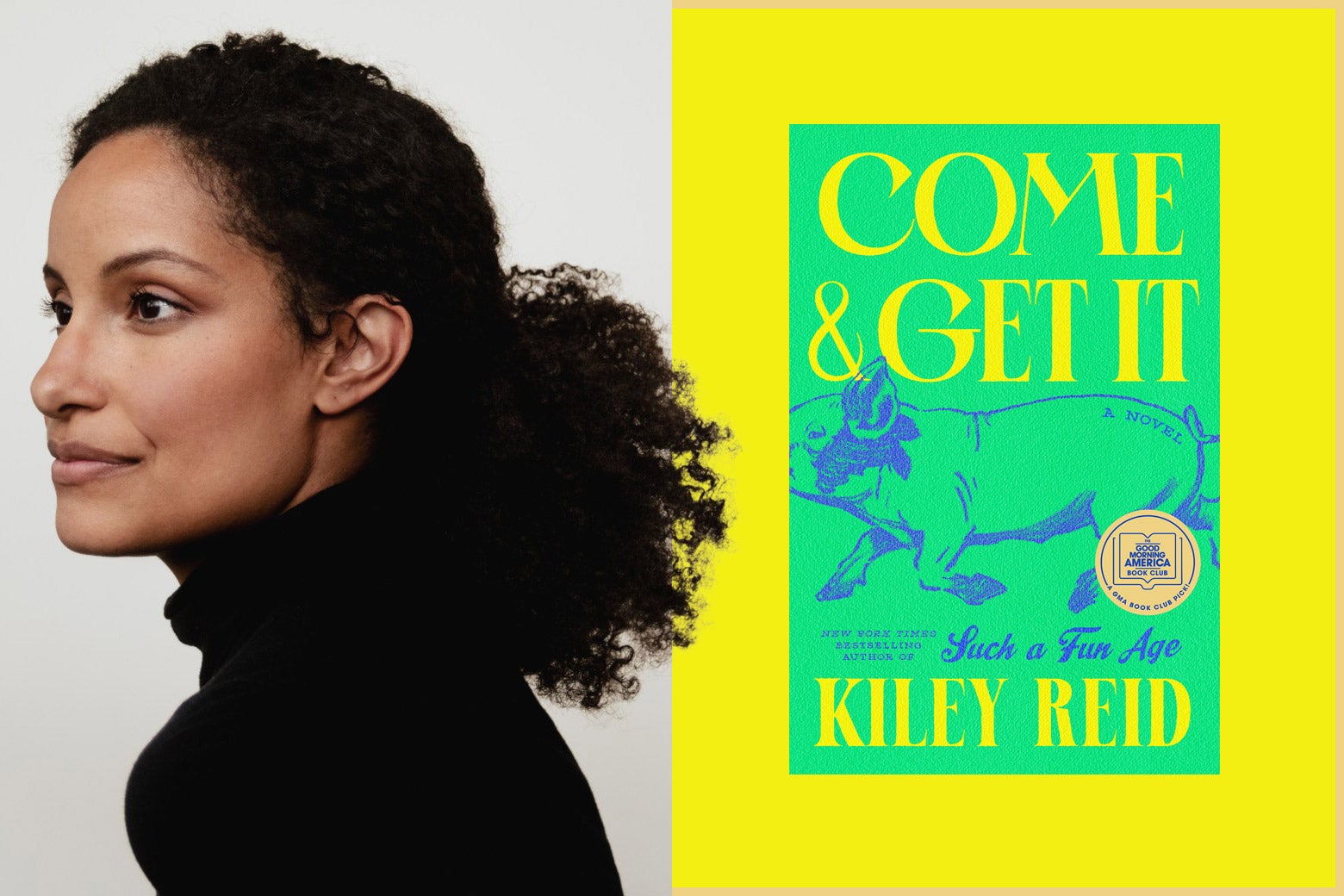

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, David Plotz talked with Kiley Reid about her new novel, Come & Get It, and discussed how Reid gets her dialogue to sound so real.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

David Plotz: I do think what makes your writing so singular and so distinctive is that you have an incredible ear. And I’m envious of it, as someone who’s been a writer for some of my life and never had an ear like that. How do you listen? How do you create these voices in your head?

Kiley Reid: It’s a bit of a game. Because as I’m sure that you’ve done, if you’ve transcribed anything because you’ve recorded something, you very quickly realize that we do not speak chronologically. We go off on tangents, we say, “um,” and “like,” and “oh my gosh.” And there’s a lot of things that we’re doing in between the things that we’re actually trying to say.

So, while I’m writing, getting hyper-realistic dialogue is really important to me, but it becomes a game of doing [two] things: One, it’s showing characters, for the majority of the book, at the top of their intelligence, showing their best selves—what they think is their best self. And number two, it’s making sure that their best self still isn’t grating to a reader.

When I’m doing interviews with students and getting inspiration, they may say ‘like’ or ‘um’ in the thousands. And so, I want to include some of those likes or ums, but I also don’t want to make fun of those students. This wasn’t a satire this time around, but I want to make it true. So, there’s a lot of give and take there.

I also think just being a writer, you need to put yourself in the position of being a listener and writing down something exactly the way you heard it. That’s the kind of things that I like to read.

Why do they have to be at the top of their game? Why is that important?

I think it’s important to be a democratic and generous writer. Otherwise, you look like you’re making fun of your characters. And I think every character can be interesting depending on the different light that they’re in. And I’m just not really super interested in fiction that says, look at these dumb kids. Especially because they’re not dumb. I want to see them at their best. And then later when they make mistakes, those mistakes hit a little bit harder.

I also feel like there’s a conjuring act here. Because as you said, I guess you wrote it in Iowa; you have lived in Philly; you’ve lived in Ann Arbor since you were in Fayetteville. But you’re conjuring up people who are just mostly Southern, and certainly are the kind of students who would be at University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. How do you get back to them when you’re not with them?

I do a lot of interviews when I’m writing. And this time around I had a research assistant, and that was incredibly useful. I probably formally interviewed about 30 people and then maybe 20 others on top of that, just making sure I was getting things absolutely right.

So, I interviewed some old students, some of my friend’s students, people who went to Arkansas, people from Chicago, baton twirlers. I interviewed a number of people.

And people always ask me, “How do you get people to tell you things?” I’m sure you know people just like talking about themselves. And people were very gracious to me, and I’m really thankful for that.