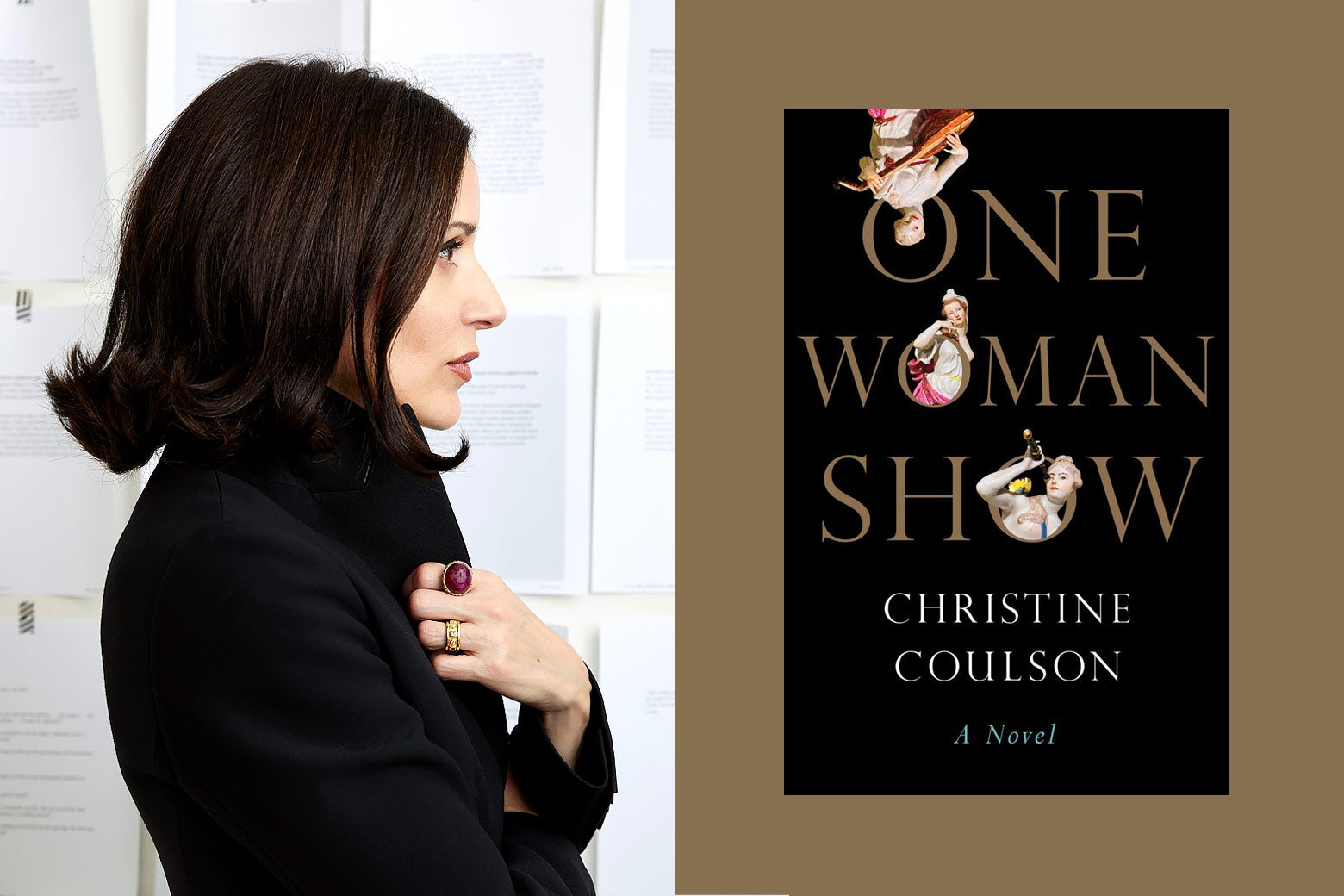

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, John Dickerson spoke with author Christine Coulson about her process for writing One Woman Show, a novel comprised entirely of museum wall labels.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

John Dickerson: So now you’ve given us a little window into your process, but give us a little bit more. You mentioned that you posted these on the wall. Help people understand how you wrote it.

Christine Coulson: I’m a very rigorous writer. So, I had the idea for this book in the spring of 2019, but then I didn’t write anything down. In fact, I’m the exact opposite of you. I don’t write anything down ever. I don’t keep a journal. I don’t take notes. I really believe the things that I need, I will remember. And so that idea—to write labels about people—sat in my head for about two years and I like that. I feel like withholding is a big part of my process. Distinctly not writing something down, but having that idea and going to visit it every once in a while, see what’s cookin’, how’s it going, and then leaving it.

So, when I sit down to write—and both books that I wrote took exactly a year to write—I go into a mode that is almost like superstitious. I eat the same breakfast at the same place, in the same chair every single day. I write exactly from 10 to 3 every day. No getting out of the chair, no breaks. Sometimes I feel like creativity is like waiting for a bus; you have to be there when the bus comes. And so, by imposing that five hours on myself, I’m there when it shows up. And I think that’s super important and it’s always worked. So, as I sit there plugging away, some days are amazing and some days, you know, not so great. I think that comes probably from going to an office for 25 years too, having that structure.

And so, I then will write something and then I tape it to the wall in a vague position of where I think [it will go]. The wall ends up to be like rows and rows of pages. I’m also working structurally with the book, but that’s a visual process for me. There are labels about Kitty, but then there are labels about what we would call, in a museum, a kind of comparative material—so, her friends in the garniture, her parents, different characters who come into the book. The rhythm of when they appeared was important. So, I would mark those pages in a way so I could see that rhythm, where that dialog was showing up, how frequently it was showing up; all of that becomes apparent because it’s on the wall. And so, I think I’m just innately a visual person. And so that is really important to me to understand how that is all working. And then I edit physically on the wall. I write on a laptop, I print those pages out, but then I stand in front of the wall and I hand edit on the wall. And then every Friday the edits get integrated and the wall gets updated, which is like my version of meditation or something. And they follow the pages back onto the wall.

So, I have images of the book as it was written. Every once in a while, there will be a sticky note where an idea comes, I don’t have a page for that yet, but it’s something that could happen. And so, the whole thing kind of unfurls itself. But I feel like that rigor, that discipline, it kind of goes with the constraint, but that’s the only way it works. It’s the only way you can do it.

You, as I recall, were an intern at the Met from the early days, right? 1990s?

I was between college and graduate school.

Did you know when you were an intern there that you wanted to be in the Met for the 25 years you spent there?

The second you get to kind of go through that door and get back to those back halls and all those gray areas that are so different from all those shiny gallery spaces I wanted in. Hundred percent.

And do you find in the two novels you’ve now written that you are touching an original interest of yours in art and the world and seeing things and exploring the human condition, which is a part of what your life in art is? That, in other words, you are touching something from that kind of formative early period, or that this is the evolution of your life in art, the way it existed for 25 years at the Met or some combination of the two?

Well, it’s a combination of “I’ve always looked at the world through works of art, through objects.” I love that. But I’m a one-trick pony. Like I can write. I’ve always been able to write, I think, because I didn’t have a lot of friends when I was little. And so, I read. All I did was read all the time. And I think because of that, I could always write. And so, when I got to the museum, I was actually hired— not as an intern, but when I came back after graduate school—I was hired to write exhibition descriptions. And that was, you know, what I could do. And that was always the thing I could do at the museum. And so, there was all sorts of ways in which I deployed that for the 25 years. But I was in the context of what I loved and what I find to be the most potent way to sort of process the world. You know, I’m not a religious person, but I find great solace in beauty and I find great joy in beauty. And so, to be in the Met every day was as important to me kind of psychologically as it was professionally. It’s just how I consume history and humanity. I don’t think it’s a real stretch to see the books I’ve written are based on the way I see the world. I don’t think the next book is going to be about, you know, the life of a plumber.

Well, now let’s not let’s not give up that constraint as a possible route to art.

It was interesting for me, having written that first novel about the Met—which was, you know, a love letter to that place and the people who you often don’t think about there: the guys who change the light bulbs and all of those people who I adore and really grew up with. But I said what I had to say about the museum in that book. And so, this was an interesting moment to kind of take my experience at the Met and apply it to a different kind of book that wasn’t actually about the museum—but was sort of the museum.