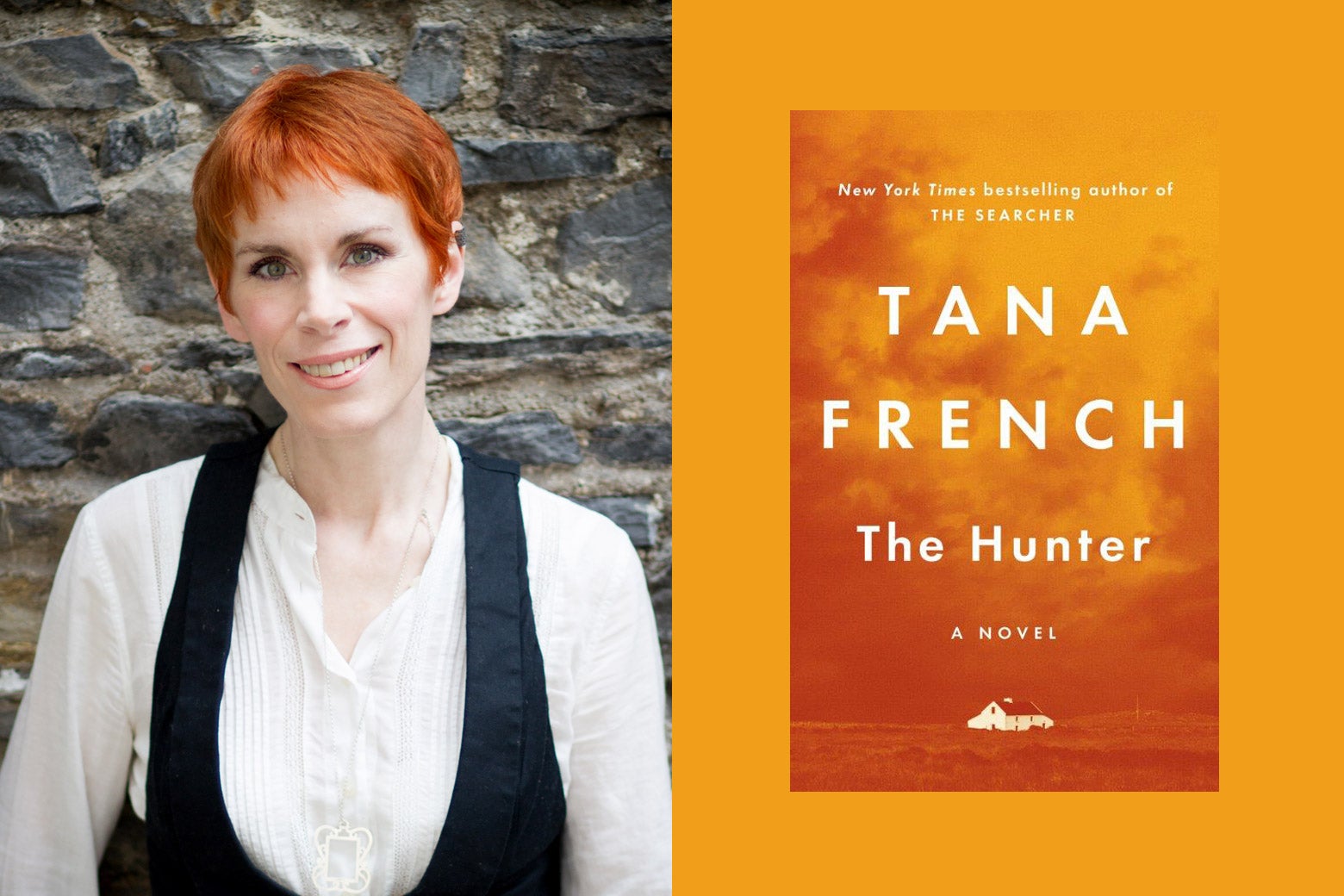

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, Emily Bazelon talked with Tana French about how the Western genre inspired her latest crime thriller, The Hunter.

This partial transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Bazelon: You live in Dublin, and you are best known for several books you wrote about the city’s murder squad. Why did you decide to move your setting and your action to, this village of Ardnakelty, a very different setting than Dublin.

Tana French: What happened was, I suddenly discovered the Western genre a few years back. Somehow, I’d never read them anywhere. They just didn’t sound like my kind of thing. And then someone whose taste I trust said to me, “you have got to read Lonesome Dove.” So, I’m like, okay. And I did, and I loved it. It’s an amazing book. And I read others. I read, you know, True Grit, on a more modern note, The Sisters Brothers. I thought they were amazing and they had so many tropes in them, but I thought it would fit really well onto the west of Ireland. Like, there’s a lot in common between the settings. They both got that sort of harsh beauty that is going to demand both physical and mental toughness from anyone who’s trying to make a living out of it. And they’ve got that sense of somewhere that’s really far removed from the centers of power, not just geographically, but culturally as well, so that the people who are living there feel like the power brokers don’t really care about them and don’t understand them. And if they want a society that’s going to be cohesive and functional, they’re going to have to make their own rules and enforce them themselves. And I thought, that’s the Western—but it also shows up a lot in drama about the west of Ireland.

And I started thinking about how certain Western tropes would map onto the west of Ireland. And in the search, I was going for, you know, the stranger who rolls into town, and maybe he’s got a bit of a past, maybe he doesn’t. But either way, he’s going to turn into a catalyst. He’s going to catalyze change in the small town, whether he wants to or not. But in The Hunter, I was thinking about a different set of tropes. I just felt like there were more things in that genre crossover that I hadn’t played with yet, and that I wanted to. I was thinking about like, Trey’s absent father, who, in The Searcher just has vanished off to London or somewhere like that. I thought, what would it do to Kyle and Trey’s budding relationship that hasn’t really solidified yet, if he came back, if he showed up—and he seemed like the type of guy who would only come home if he had a get-rich-quick scheme—if he had something to bring that would make him the hero and that would make him money?

I started thinking about the gold rush trope that shows up in so many Westerns. You know, there’s gold in them there hills, and weirdly enough, it doesn’t sound like Ireland would be the kind of place where a gold rush would fit in. But it sort of does, because when Johnny says there are all these ancient gold artifacts that have been found in Ireland, there really are. There really are just huge numbers of them in the National Museum. And there have been little gold rushes over the centuries. Right up until now, you still get companies finding a seam of gold somewhere in the mountains and try to capitalize on it. So, I thought, well, what if Johnny comes home with a plan to find gold in them there hills, and took it from there?

You know, one of the things that I love about the gold rush part of the story, is that it makes the book feel old and new at the same time. Like, there are a lot of cultural references to right now, to the internet, to Instagram. We know that it’s now, but because they’re looking for gold—which, yes, evokes the 19th century in California and people panning in the river; you even have them out there in a river in one scene—it feels sort of timeless. And I wonder if that is also one of the appeals of this village setting, that it’s in the modern world, but it’s also kind of apart in some way as well.

Well, it’s one of the things I like about the west of Ireland, where it is modern—these are not old-fashioned people stuck driving horses and carriages—but it’s very deeply rooted. You know, you get people on land that their ancestors have farmed for as far back as anyone can remember. You have reminders of the past everywhere. You have little farm and cottages popping up all over the landscape that were abandoned in the 1860s during the Great Famine, and they’ve just been left to tumble down and have nature take them back. So, there are reminders of the past. It’s very much present. The divide isn’t as solid and final as it can sometimes feel in cities. Its layers are very intertwined and very present at the same time.