This is part of Time, Online, a Future Tense series on how technology is changing prison.

The other night, I tried to send my girlfriend, Faye, a goodnight text, but the unreliable messaging app on my prison-issued tablet froze. I restarted the tablet to no avail. The same glitch occurs most nights between 7 and 10 p.m., the peak hours of tablet usage at the prison where I’m incarcerated in North Carolina. Once again, I gritted my teeth, preparing for a long night without connection to the person I love.

Faye works the graveyard shift at a hectic Florida hospital. I love leaving lighthearted messages to make her smile during her lunch break. We’ve been communicating off and on for 10 years while I’ve been serving life without parole. We used to rely on weekly letters, because a 15-minute phone call cost nearly $2. But in 2019, my prison launched a tablet pilot program which gave us access to e-messaging.

Now, Faye and I text three or four times a day through the app. She messages me to vent about difficult patients, brag about cash saved with coupons, and grieve about the struggles of being a single mom seeking financial stability. Even though I’ve been in prison for 22 years, messaging Faye offers me the illusion of being a part of her life in the free world. I hear about the most important details of her days in real time, and I can play an active role in her life when she needs me most.

For as long as there have been prisons, relationships have found a way to breach prison walls. When I was processed into the system in 2002, I was sent to a prison that had no access to phones; letters and visitation through a dirty plexiglass window were my only links to the outside. At the time, most other North Carolina prisons allowed prisoners to make two phone calls a month, but an officer stood beside the phone while men described the atrocities of incarceration to their loved ones. As is always the case in prison, we did what we could with what we had.

But now, many incarcerated people can message their partners—and vice versa—throughout the day and night. The tablets that allow them to do so, developed by private companies that charge for their use, are changing the dynamic of prison relationships. Today, incarcerated people obsessively log on to their tablets like teens awaiting DMs from crushes. Prison pen-pal sites advertise someone’s e-messaging profile. On TikTok, people with incarcerated partners post tips for using the tablets: Don’t worry if they don’t respond even though the platform shows they’re online; they’re not ignoring you, they could be on another app.

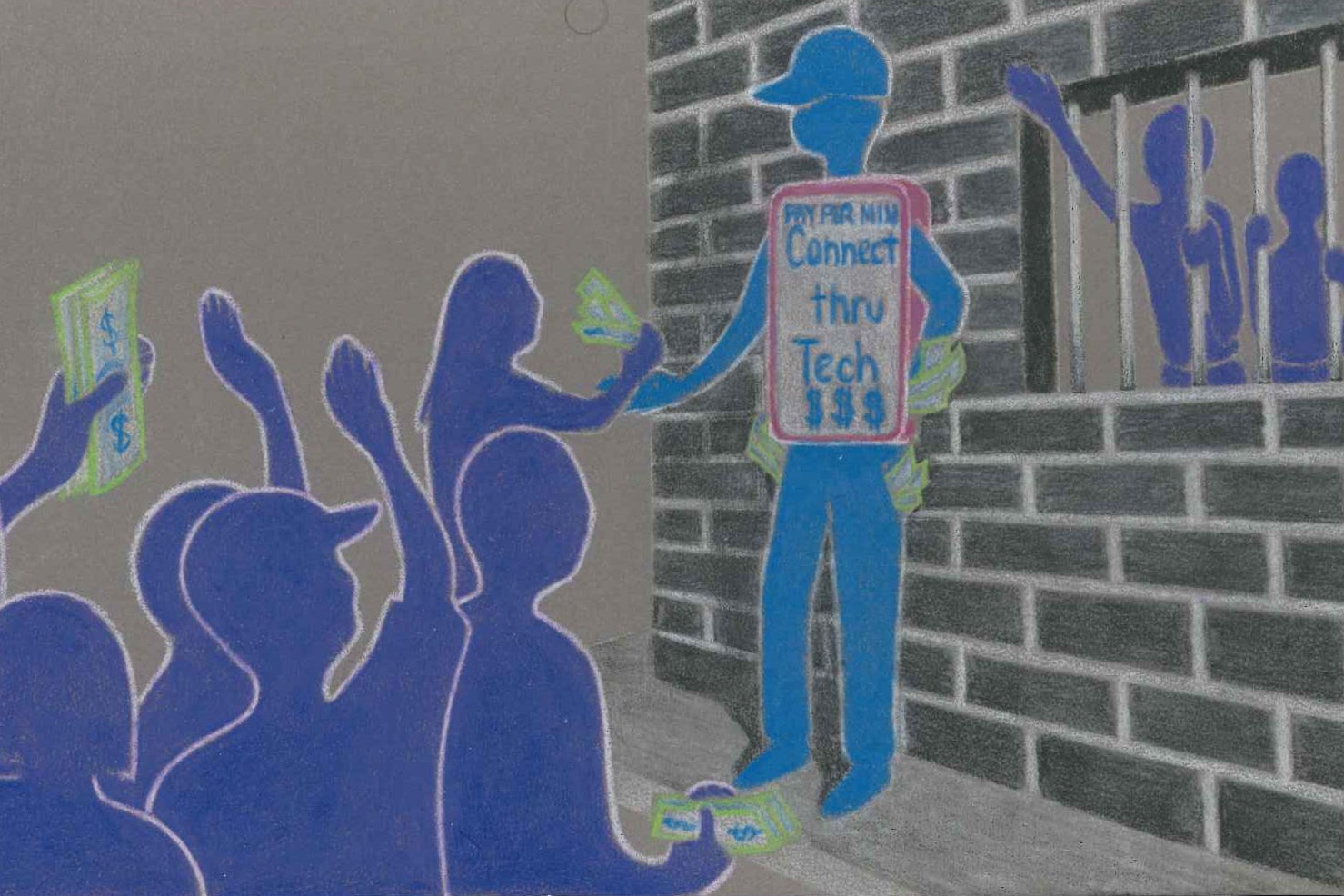

E-messaging can facilitate connection and growth during incarceration, but exorbitant fees and shoddy service can also hinder relationships instead of nurturing them. More than 40 states currently offer electronic messaging through for-profit companies, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, and these companies often share a portion of their earnings with the prisons that allow them to operate.

Two companies dominate the market: ViaPath (formerly GTL) and Securus, followed by Corrlinks. These companies hold statewide monopolies and charge varying fees to provide the same service in different states. For example, both California and Oregon use ViaPath’s messaging system, but families of incarcerated Californians pay only $0.05 per message, whereas Oregonians pay $0.25. In Arkansas, Securus users pay $0.50 per message; in Connecticut, messaging is free. Maintaining a relationship has a different price depending on where you sit.

In North Carolina, we use ViaPath tablets, which are preloaded with the messaging app GettingOut. We generally pay between $0.01 and $0.03 per minute of tablet use; free people who message us pay more. Each message Faye sends me costs $0.25, whether it’s a one-word text or a picture of her twin daughters playing volleyball. To add $15 to her account, she must pay a fee of $3.81.

Kwamé Teague is well versed in the cost of communication. He’s been incarcerated for nearly 30 years. Before instant messaging, Kwamé relied on phone calls to connect with Jay Rene Davis, his partner of eight years, whom he met when Jay Rene wrote him a letter after reading his book, The Adventures of Ghetto Sam. Kwamé still spends about $100 a month calling Jay Rene several times a day, at $1.81 per 15-minute call, because the pair hosts a podcast together. But now, e-messaging helps make communication more fluid.

“Texting gives us an opportunity to connect throughout the day,” Jay Rene told me during a phone interview. “If I’m thinking about him, I don’t have to wait for a phone call. I like being able to say what I feel when I’m feeling it.”

Cara Sutton is willing to pay whatever it costs to message her ex-husband, Michael Sutton. They married after meeting in the Army in the ’90s and divorced five years later. But they reconnected when Michael landed in prison to serve a 25- to 32-year sentence. Before instant messaging, they rekindled their romance through letters and phone calls, because Cara lives in a different state and cannot visit frequently. She spends upward of $200 a month connecting with Michael.

When calling Cara, Michael used to worry about other prisoners in the cellblock eavesdropping on his conversations. Texting gives him a semblance of privacy, enabling him to express emotional vulnerabilities that he once feared men would exploit if they overheard. But ultimately, that privacy is an illusion.

Prison officials routinely read incoming and outgoing messages, and prison apps automatically screen for potentially problematic content. Messages can be flagged for seemingly profane or violent language, or other policy violations. But the screening systems rarely account for the context of the message. Knowing someone monitors my conversations makes me think twice about what I text. I don’t want to face backlash for criticizing staff or a particular policy. I also coach my loved ones not to text anything they wouldn’t want a room full of people laughing at or scrutinizing.

In North Carolina, tablets are classified as “behavioral management tools,” which means prison officials can restrict usage at a whim, without following the disciplinary procedures that govern access to other “privileges” like commissary or unit phones. In July, for example, after a few people were caught hoarding cleaning supplies, tablet use was restricted. Instead of just punishing the culprits, none of us could message our loved ones, even though most had committed no wrong. Infuriated men argued over who was next to use one of four wall phones, now the only instant connection to the outside world for the 108 men housed in my cellblock. On the way to chow, I walked past someone gesticulating wildly while cursing at a corrections officer. He’d been waiting for a text from his sister updating him on the status of his hospitalized mother, and without tablet access, he had no way to know if she had made it out of a recent surgery.

This feeling of disconnection is familiar to Cierra Cobb. Her husband Jeffrey Cobb is housed in a maximum-security prison where he can only use tablets for a few hours a day. Cierra spends about $250 a month messaging Jeffrey, and adding credits to his account so he can respond. They often struggle with glitches in the messaging app that make it impossible to send messages.

“I get so sad when I can’t talk to him,” Cierra said in a phone interview. “I wonder if he’s safe. We send 15 to 20 texts a day because that’s all we have, and when I can’t reach him, I feel helpless.”

All the couples I spoke to appreciated the convenience of e-messaging, and the way it had improved their relationships by facilitating communication. But they all also struggled with the predatory cost. Like many incarcerated people, I work as a janitor, earning $2.80 a week. I rely on donations from my family to survive. Money meant for deodorant or toothpaste often purchases tablet time. I’m serving life and will most likely die in prison, but communication helps me feel human within a concrete mausoleum. The alternative of disconnection is paralyzing.

One recent night, Faye had trouble logging into the GettingOut app. When she finally got in, she wrote me a message. “I know it’s not your fault if I don’t hear from you tonight,” she typed, “but I’m sure I’ll get a text in the morning.” The message felt like reassurance of the bond instant messaging has helped us develop. The service is unreliable, but we rely on it to keep us connected. I text Faye about fights I avoid, nauseating chicken patties at chow, and how her presence in my life humanizes me. Losing immediate contact with her, now that I’ve grown accustomed to it, is my greatest fear. I can’t imagine being completely cut off from her world.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.