In 2021 the writer then known as Luc Sante—author of the classic 1991 urban history Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York—sent an email to a group of friends and colleagues. In it, she explained that she was in fact Lucy Sante and would now embrace the gender identity she had suppressed for the previous 66 years of her life. The most startling thing about this news wasn’t Sante’s transition, but the fact that she had put it off for so long. In her captivating new memoir, I Heard Her Call My Name, Sante mentions that, while living in New York in the 1970s and ’80s, she had been close to the photographer Nan Goldin, a celebrated portraitist of the downtown gay and transgender communities. Sante describes herself as first and foremost a “bohemian,” a type of person of which there are “vanishingly few” these days. Proud gender nonconformists, drag queens, and the people who admired them were all around her during her New York years—yet, in the midst of what was surely the most accepting environment available at that time, she still didn’t feel free to be herself.

Apart from Sante’s age when she announced her gender identity, there isn’t anything particularly unusual or new to her transition story. Technology played a pivotal role, from an app that feminizes selfies and showed her the woman’s face she had so long denied to the online communities where she sought advice and support in coming out. She describes the physical effects of taking hormones, the process of constructing a whole new wardrobe, the stress her transition imposed on her long-term relationship. What makes I Heard Her Call My Name extraordinary aren’t the events Sante describes but the way she describes them. Her writing remains as perceptive, elegant, and striking as ever, and furthermore it is fearlessly honest—a quality that often seems almost as rare as Sante-style bohemians.

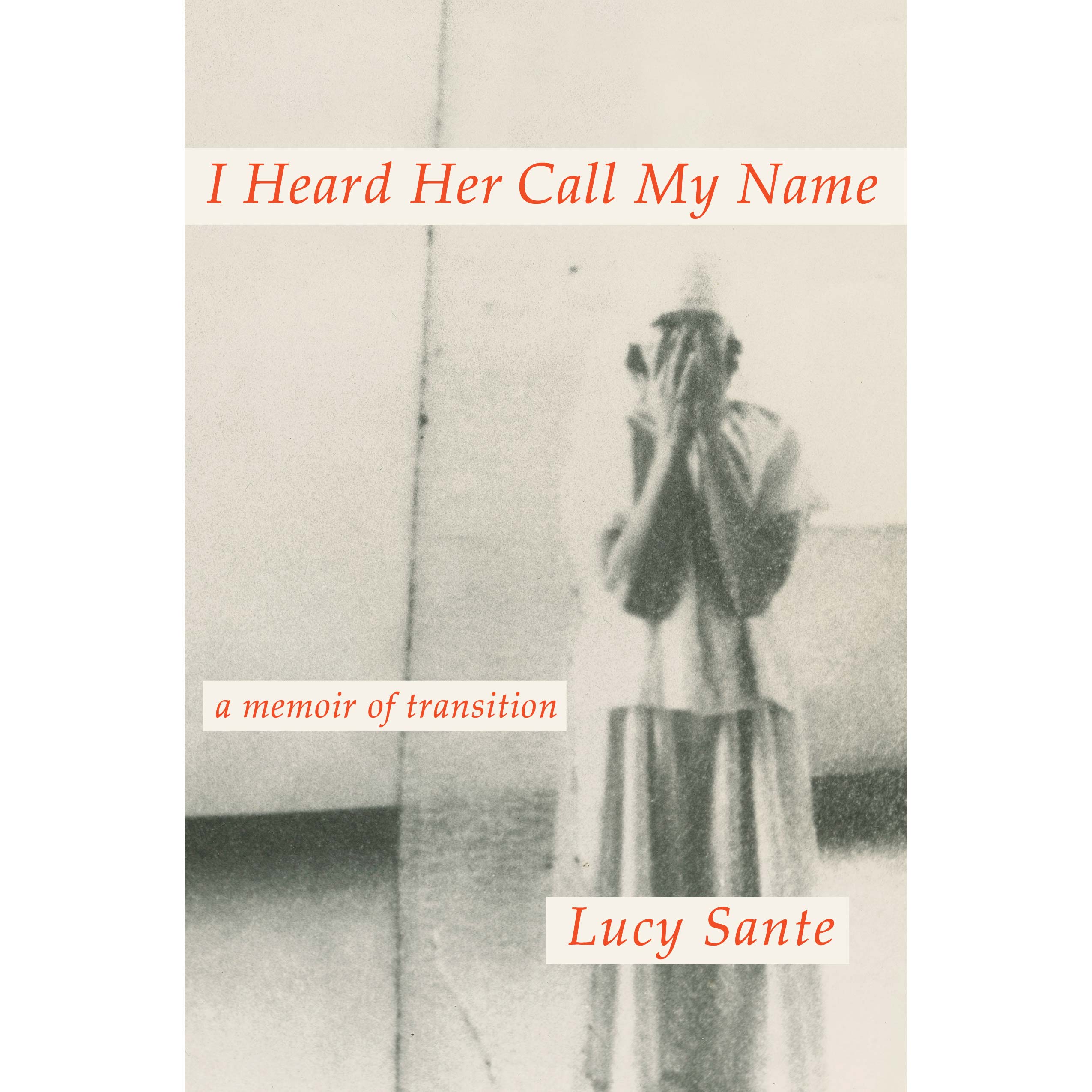

I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition

By Lucy Sante. Penguin Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

“I’m allergic to theory,” Sante writes, “and even more to the kind of shibboleth rhetoric (and its principal by-product, a defensive posture) that pervades much—though by no means all—of trans writing.” This pertains to the concepts in I Heard Her Call My Name as well as to the book’s language. Sante frames the book as a double memoir, one part describing her conventional biography—all of it lived in the persona of Luc—and the other recounting her progress since her “egg cracked” (one of the instances in which she does use trans lingo—presumably not of the shibboleth variety). “Luc’s” history is interesting in its own right: The Belgian-born only child of indecisive Belgian immigrants, Sante spent childhood pinging back and forth between New Jersey and Belgium, the country her mother loved and forever yearned for.

Luc was a foreigner who felt truly at home only in New York City, the version of it haunted by the crime, social chaos, and economic woes of the 1970s. It was a run-down but still thrilling city where misfits, artists, eccentrics, and adventurers could afford to live, albeit in “hovels.” “Aside from the inevitable stereo,” Sante writes of these apartments, “they contained little in the way of current consumer goods; almost everything we owned was secondhand and likely scavenged.” Still, she makes it sound exhilarating. Luc was a punk aesthete whose friends included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jim Jarmusch, the Bush Tetras, Lux Interior, Darryl Pinckney, and Elizabeth Hardwick. Luc wrote, and Lucy still writes, for the New York Review of Books. It has been a life, if not of riches, certainly of an enviably authentic late 20th-century coolness.

Despite being surrounded by every variety of rebel and free spirit, Lucy hid behind the facade of Luc—a male persona she describes as “saturnine, cerebral, a bit remote, a bit owlish, possibly ‘quirky,’ coming very close to asexual despite my best intentions.” She was and is deeply and comprehensively attracted to women, toward whom she has felt an almost abject reverence. (She often writes of not “deserving” to be one.) “I had tried so hard for so long to be a heterosexual man,” she writes, “that the need to behave like one took me over like a puppeteer whenever I found myself in the presence of a woman I found attractive.” But maleness itself, “with its acrid musk, its stubble, its needful dangling genitalia, its oafishness and clumsiness, its sense of mission and conquest,” reminded her only of “the aspects of myself I most despised.”

Sante’s mother, a stringent Catholic, openly mourned Marie-Luce, the stillborn daughter who preceded Luc. “She often called me by feminine diminutives,” Sante writes of those early years. “I’m certain my mother wanted me to be a girl.” She feared men, and longed for a child who would be an extension of herself. When Sante was young, her mother “searched my room on any pretext and read every bit of writing she found there. She wanted an account of everywhere I went and everyone I met.” Following each of two events signaling Sante’s independence—going off to college and getting married—her mother had nervous breakdowns and had to be hospitalized. She felt her child had betrayed her by growing up, and she never forgave Sante for “leaving” her. To the end of her mother’s life, Sante writes, “we hated each other so intensely it was almost like love.”

Did this fierce, tortuous relationship contribute to Sante’s gender dysphoria? Maybe? Probably? Sante seems to think so but shows no interest in determining exactly how much—or in arguing that she was simply born that way. Making categorical declarations about such unknowable things is an activist’s proclivity, and Sante lacks it. I Heard Her Call My Name is a revealing memoir, yet a resolutely private one as well, concerned only with documenting how this life and transition have felt to a single, idiosyncratic human being. “I don’t wish to be a spokesperson,” Sante writes in the book’s final chapter. She is less interested in establishing what made her what she is than she is in delivering a truthful accounting of what it has felt like to live almost seven decades denying “the consuming furnace at the center of my life.” The shame and unworthiness she still feels (despite supportive friends and many years of therapy) serve as reminders of just how hard it can be to shake off the bindings laid on during our childhoods.

As Sante tells it, her life as Luc combined the performance of a male, intellectual identity and the relinquishing of almost every major decision to her female partners. “My marriages were succeeding monarchies,” she writes in one bravura paragraph that recapitulates lists of the lifestyle markers of the ’80s (“We ate at restaurants where you were served seven squid-ink ravioli on a plate the size of a bicycle wheel”) and ’90s (“We joined a food co-op and experimented with previously unknown leafy greens”). “I underwent all these things passively,” Sante writes; “they were weather. But at the same time they seemed alien, and my participation ceremonial, as if I were visiting a foreign country and for diplomatic reasons had to undergo all the observances, however inexplicable.”

While Sante’s particular predicament was unusual, this sensation of falseness will be familiar to many. You don’t have to suffer from gender dysphoria to feel that you “could mimic this or that specific behavior, but couldn’t sufficiently understand the underlying logic to knit the behaviors into a convincing personality.” A paradox of this breed of confessional writing, when it’s done as well as Sante does it, is that the more precisely and frankly the writer describes an individual experience, the easier it becomes for readers to recognize it as similar to dilemmas of their own. Even the one area in Sante’s life in which she felt confident, her writing, became contaminated by her unwillingness to face herself. “In the absence of any other notably masculine qualities,” she observes, it was writing that “became the principal signifier of my male identity, and gradually my social personality became coextensive with my work.” In time, “my work didn’t reflect me; I reflected it. So Luc was in many ways a walking byline.”

Today Luc remains a presence that, Sante says, “I sometimes like to think of as my sad-sack ex-husband,” a hilariously homely and even fond way of accommodating a shucked-off identity. Sante’s writings have meant so much to so many readers it would be wrenching to have to dismiss them as the product of a person so self-deceiving they merely served to prop up the fraud. There has always been much truth in her work, flourishing like those renegade artists in the squalor of 1970s New York. And now there is even more.