Stephanie Land’s first memoir, Maid, about trying to support her toddler daughter on housecleaning wages in the Pacific Northwest, became a Netflix hit series starring Margaret Qualley. This month, Land has a new book out: Class: A Memoir of Motherhood, Hunger, and Higher Education. Class is set during Land’s senior year of college, at the University of Montana in Missoula, at a time when Land was a nontraditional student in her mid-30s and her daughter Emilia was in kindergarten. (Her daughter now calls herself “Story,” but remains Emilia in the book.) Land and Emilia were on food stamps, but a recertification led to a reduction in the already-low monthly amount they were allotted, and they had trouble getting enough food.

Some memorable sections of Class describe Land’s hunger—especially when she became pregnant with her second daughter—and Emilia’s emerging relationship with food and eating. I asked Land to speak more about the way scarcity affected both of them—and how things changed after Maid sold, and turned Land into a sought-after writer and speaker on issues around poverty. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rebecca Onion: You write that because of the lack of food in your house, Emilia developed certain tastes, or had certain things that she learned to like.

Stephanie Land: I couldn’t afford to buy produce, I couldn’t afford to buy a lot of vegetables or fruit, or anything like that. The produce that I did get was things that were very drastically on sale. I couldn’t afford to buy, like, kale and asparagus. And her diet didn’t vary all that much. They say you’re supposed to introduce foods three or four, up to five times, before a child will actually eat it. I couldn’t afford to do that—I bought food that I knew that had a long shelf life and was cheap.

It took Story a long time to enjoy eating vegetables. It’s really the last five years she’s started to expand what she’ll eat. There was this anxiety around food. I never got outwardly mad at her for not finishing her food, back then, but I mean, it’s hard to hide your stress all the time, and so, when kids naturally do what they do—it’s like, they love this one flavor of yogurt, so you buy it the third time, and they suddenly don’t like it anymore—I mean, that’s frustrating no matter what income level you’re at. But for me, it was just like, Well, this is for you, this food is for you, I bought this for you! Because I’m not out there buying myself a Go-Gurt! She picked up on a lot of that.

Did you feel guilty about that at the time? Or were you just like, This is what’s happening? I ask as a mom who constantly feels guilty about what my child will and will not eat!

At that point, I mean, that had been our whole life. And we might’ve had periods where it was better, based on if I was able to work more, or I was in a relationship, or something like that. But I mean, for the most part, that’s just how it always was. I mean, the times that I felt guilty about it is when she would go to other people’s houses and they had just a bunch of fresh fruit or some healthier snacks, and she got all excited about that, and I couldn’t afford to do that.

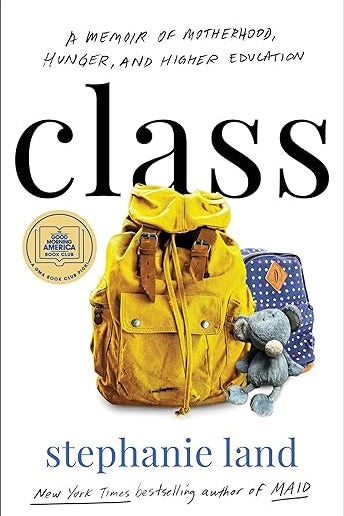

Class: A Memoir of Motherhood, Hunger, and Higher Education

By Stephanie Land. Atria.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

You said in another interview that someone wrote to you after reading the book and said that you let Emilia have too much ice cream, which I thought was such a classic “person on the internet” response.

I think she was saying I was being too frivolous with my money—if you’re that poor, then you shouldn’t be spending money on ice cream. At one point in the book, I get a bunch of back pay in food stamps, because I had been pregnant, and it took a long time for that paperwork to go through, and then, I suddenly had like, $400 or something in food stamps, and I went out and bought myself a steak. I had never really cooked meat at home, but I just really needed meat with this baby that was growing—she became a child who still loves meat. And this person shamed me for that, too, that I was spending all my money on ice cream and steaks, and it took me a while to figure out what steak she was talking about. It was one that I picked up for like three bucks.

Your book ends before your life changes, through selling Maid. I’m curious, with more financial stability in your life, how the change in having more types of food around, or more access to food, might have changed your daughter’s relationship with eating and your relationship with eating.

It’s still kind of hard. I mean, it’s really hard for me to waste food. My husband does the grocery shopping, for the most part, and I still shop a lot differently than he does. I still purchase a lot less. I don’t buy a whole bunch of things at once. My second daughter, Coraline, never really lived with food insecurity—I finally was off of food stamps at the beginning of 2016. But one of the things that really changed was, we moved into low-income housing, and so I had this apartment that was only $430 a month, but it was like a block away from this health food, organic store. Originally I never even set foot in it, because it was the expensive fancy store in town. I started going there when I would strap Coraline into the Ergo carrier thing and walk to the store when she was taking a nap. And just to be able to go several times a week and buy very small amounts of really high-quality food, we ended up eating really differently. Once I started buying the higher quality food, we were full longer, it was just more nutrient dense, and wasn’t full of salt and sugar, and all of that. They always had staples that were the cheapest price in town, like milk, eggs, and sugar and flour. And I mean, there was definitely like, the little jars of pesto and shit that I couldn’t afford, and I still don’t buy, because it’s just ridiculous. But it was interesting to me how much it changed our way of eating, and just our general health, to have access to a store that had a higher quality of food.

You wrote that Emilia didn’t like to eat leftovers. Is that still not a thing?

Neither of them do. Coraline will eat leftover spaghetti if it’s not presented as a leftover, but no, Story still doesn’t really eat leftovers. She’s really good about cooking, she makes herself her own food a lot, and she’s probably the healthiest eater out of all of us. But she’s really good at cooking herself just the amount that she’s going to eat.

Correction, Nov. 27, 2023: This article originally misspelled the name of Land’s daughter Emilia.