This essay has been adapted from Trash Talk: The Only Book About Destroying Your Rivals That Isn’t Total Garbage by Rafi Kohan, available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group Inc.

Cassius Clay sits at a microphone with Bundini Brown by his side. The year is 1963, and the 21-year-old boxer is giving a press conference in Toronto on Canadian TV. It’s a fascinating scene for several reasons. First, the two men, who will go on to develop one of the most important relationships in boxing history, are still just feeling each other out. There’s a courtship vibe in the air, as trainer Bundini, a new addition to Clay’s coterie, claps the boxer gently on the back—it’s an affectionate gesture, but also a kind of trial balloon, like a young man yawningly stretching his arm across the shoulders of his date. At another point, Clay turns the questions on Bundini, interviewing him about his time with Sugar Ray Robinson.

He asks, “Was he as great as me?”

At this early date, Clay is clearly aware that his words can be weapons in the battle for public attention. But there is still something unpolished about the young fighter. It’s like he’s trying out a new act and waiting for the test-screening data. His answers lack the self-assured authority that will come to command a room so easily as Muhammad Ali. He looks down frequently, breaking eye contact while he speaks. When asked if he was “as volatile” as an amateur as he is as a pro, he responds, “No, I wasn’t. At that time, I didn’t realize how great I was.” Which elicits laughter from the press corps.

Is he being serious or not? they surely wonder. Perhaps Clay is wondering, too. He looks down again, trying to hold back a smile. Before long, he loses the room.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

It’s not his fault, exactly. But when Canadian boxer George Chuvalo, who Clay had said he would fight before taking on Sonny Liston, bursts into frame, in an impromptu public ambush, Clay finds himself suddenly on his rhetorical heels. Wearing a patterned frock and a wig—a reference to the nickname Clay has given him, “the Washerwoman,” which was meant to describe his flailing fighting style—Chuvalo interrupts the press conference to accuse Clay of ducking out of their bout. Chuvalo brings a handful of demonstrators on stage along with him who hold protest placards that mockingly call out the future heavyweight champion as “Cautious Clay.” As this happens, Bundini smiles and knocks on the table with his fist, in seeming appreciation of the spectacle.

Clay has no choice but to engage. “The way you look, who wouldn’t run?” he says, doing his best to wrest back the narrative reins while responding to Chuvalo’s charges of cowardice. Clay stands up and slaps at Chuvalo, less playfully than usual. He snaps, “Get back, chump.”

But he is no longer in control, and he knows it.

In truth, the whole thing drags on too long, and gets a bit awkward, with no obvious endpoint. Clay can sense it. You can see it in the way he starts nervously scratching his chin and the back of his neck, a newfound tic. Steeped in discomfort, he sneaks furtive glances over at the press, trying to decipher how this is all coming across—and what he looks like—from the other side of the camera lens.

He barks, “Cut the film off so I can do something.”

But he’s not looking to fight. He’s looking for an out.

Clays looks over at the press again.

He says, “Cut your camera off.”

But it just keeps going.

Fast-forward eight years to 1971. A heavyweight title, name change, and boxing suspension-slash-reinstatement later, Muhammad Ali is ready to take on Joe Frazier in an attempt to reclaim the championship belt that was stripped from him in 1967, when he refused to be inducted into the army. It will be their first of three fights and billed as the Fight of the Century. At a press conference ahead of the bout, Ali boasts in no uncertain terms about his impending victory. (In reality, Frazier would win via decision.) Ali scrunches his forehead with a kind of indignant certitude and projects his voice as if he’s in the center of a large lecture hall. With Frazier in almost comically close quarters—the men are close enough to kiss—Ali compares the upcoming matchup to an amateur taking on a professional. He dismisses Frazier as “easier to hit” than past opponents. “I predict the fans will be angry,” he says. “They’ll be mad at the experts for misleading them so much.”

When Frazier tries to get a word in—to tell the gathered media that Ali is spouting “nothing but a bunch of noise” and that he (Frazier) is going to end the fight before it goes the distance—Ali slips a banana peel in his path.

“He’s agitated, he’s agitated,” he says.

And the press goes wild with laughter. Just as he knew they would.

While Ali always recognized the importance of how he was perceived—and that he could wield language in order to help shape that perception—there’s something more sophisticated about this version of the boxer and the way he handles this press event, compared to the sheepish aggression that defined his response to George Chuvalo or the raw and raging outbursts he put on display against Sonny Liston before their title fight. From the very first camera shot, it seems clear Ali is in control against Frazier, whom he has been disparaging as a coward and an Uncle Tom for years. Ali barks, he needles, he jumps out of his seat when a particularly noisy exchange is in need of punctuation. At one point, he even baits Frazier into accepting a side bet that the losing boxer will crawl across the ring in submission to the victor. “Write it!” Ali then screams to the reporters. “He says he’s going to crawl.”

What opponents like Frazier never seemed to realize is that, by engaging with Ali in this way—by trying to reason with him in any way, really—they fall into the man’s rhetorical traps, which wind like a maze through a fun-house logic of his own creation. Even when Frazier was unanimously declared the winner of that first bout, he couldn’t escape Ali’s exasperating logic system. After the bruising match, both men were sent to the hospital. But while Frazier spent the better part of a month convalescing, Ali discharged himself almost immediately, refusing to even stay the night, and used that fact—and the insinuation that he had done the most damage—to claim he was the real winner.

For former MMA fighter and UFC trash-talk pioneer Chael Sonnen, the prefight press conferences were almost as important as whatever actually happened in the cage. “If I went to one of those things and somebody else got more questions, I’d be depressed,” he says. “I’m keeping track of who’s getting the most questions. I’m keeping very, very good track.”

Sometimes Sonnen would plant questions with friends in attendance, just in case the focus of the event wasn’t adequately flowing in his direction. “I’ll get my phone out and start texting people in the audience right then,” he says. “ ‘Ask me this. Ask me this. Ask me this.’ ” Critics would accuse Sonnen of trotting out prepackaged lines. But he never saw the issue with that. “Yes, I have a pre-canned answer. For God’s sake, I wrote the question.”

Sonnen believed such public appearances were all about preparation, and he’d workshop his responses—while driving in the car, while shampooing his hair, while doing whatever. “I’d just be thinking about different questions, and how I was going to answer it, and how I was going to spin it, and how I was going to bring the mud on my opponent and two more opponents for the future,” he says. Sonnen would imagine himself to be on live TV, or in front of a press scrum, or sitting opposite champions like Anderson Silva, as he fine-tuned the phrases that would spill out of his mouth and into the headlines. “I’m like Jon Jones, I sound like Sean Combs, and I got trombone-size stones like John Holmes,” he’d say. Or: “I don’t deserve title shots. Title shots deserve me.” Or: “I’m the reason Waldo is hiding.”

He did his homework, to be sure. But for Sonnen, trash talk was never a chore. It was an opportunity. He was a natural performer, with good comedic timing and a rascal’s instincts. At the press conference ahead of his 2017 fight with Tito Ortiz, for instance, Sonnen lights up with an impish glee as he fucks with his opponent. In response to Ortiz accusing Sonnen of talking his way into big fights but failing to perform, Sonnen says, “Tito always says I’m using my mouth to get my opportunities. The only person I know that made money using their mouth is his ex-wife,” in reference to the porn star Jenna Jameson. The crowd goes, “Oooooh.” It’s a gut-punch of a line, and you can feel the air go out of the room.

At first, Tito responds by fact-checking Chael: the two were never married. But then he stops. There’s a brief pause, and in that moment, Ortiz, who’s built like a thick, bald rifle round, realizes the irrelevance of such a clarification. He says, “You’re a fucking punk, dude.”

Sonnen smirks and pumps two thumbs at himself, as if to say, Ain’t I a stinker?

Wrestling broadcaster, announcer, and journalist Jason Bryant has a term for Sonnen’s brand of dizzying press-conference bullshit, which he’d employ to both manipulate the media and stagger his opponents verbally, relegating them to second fiddles in the eyes of reporters: Chael logic.

“Chael lives in a world of half-truths with his smack talk,” says Bryant. “He just says these things that are absolutely off-the-wall. He puts you backpedaling, trying to disprove his Chael logic with real logic. And then you see the game at work.”

Chael logic was being “undefeated” despite having lost more than 10 times. It was insisting he’s the headliner “with my encore presentation coming after that” on those occasions when his fight wasn’t the main event. It was telling the media that the authorities “must have caught me on a low day,” when a drug test following his first fight with Anderson Silva revealed too much testosterone in his system. (In 2012, the Nevada State Athletic Commission would grant Sonnen a therapeutic-use exemption for testosterone. Two years later, however, he would test positive for a handful of banned substances, leading to a two-year suspension.) And it was definitely his claim that he didn’t realize he was conceding the fight—and not just the round—when he tapped out to Silva, at the end of that first bout, which Sonnen had dominated to that point. In this twisted logic, Sonnen exemplifies the tongue-in-cheek teachings of Stephen Potter, author of The Theory & Practice of Gamesmanship or the Art of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating, who writes that “the good gamesman is never known to lose, even if he has lost.” Like Ali after that first Frazier fight.

Bryant says of Sonnen, “He makes these outlandish statements. He could say, ‘No, the sky is red. All of you need corrective lenses. I am the only one in this world that has had corrective surgery to see what color the sky really is! And if you don’t believe it, you are stupid!’ That is Chael logic.”

Another way to describe it would be: gaslighting. Don’t believe your lying eyes.

On the one hand, Sonnen could never understand how seriously people would take these claims—why would anyone engage with his obviously flawed and squirmy arguments? Didn’t they realize this was all an act? On the other hand, Sonnen made you believe that he believed. And that level of sincerity was disorienting. Of his tap-out claim, in particular, Sonnen says, “I did it with a straight face and they didn’t know what to do. Even Anderson didn’t know what to do. Dana [White, CEO of the UFC] didn’t know what to do. Dana thought I was crazy. I had them all believing it.” Sonnen never broke character, and that made him inscrutable, per Bryant: “When you throw something out there and it comes across as so sincere, it makes you second-guess. Well, is he right? Is the sky actually red?”

What almost all great trash-talkers have in common is this: they find a way to force opponents to inhabit their world of often infuriating logic, regardless of the sport. In their basketball battles, for instance, the high-flying scorer Russell Westbrook and defensive pest Patrick Beverley would go back and forth trying to change the terrain of rhetorical engagement.

Westbrook let Beverley know how many points he’d scored on him; Beverley would respond by reminding Westbrook how many shots it had required for him to get there. Longtime UConn women’s basketball coach Geno Auriemma has described a similar dynamic between former Huskies stars Sue Bird and Diana Taurasi. “That’s the essence of Diana and Sue,” Auriemma said in a 2018 New York Times story about the players’ relationship. “Sue will tell you how consistent, how many times she wins, consistently. And Diana’s response is, the one time she beat you, will be the only thing she talks about, ever.”

Former NBA All-Star Danny Manning refers to this as “finding a way” to talk smack. Even when he was matched up against a renowned defender and shot-blocker, he’d chide that player by saying, “Oh, you missed that one,” or, “You didn’t block that one,” on those occasions when he got off a successful shot attempt. When Rayford Young (father of Trae) played against Tyronn Lue in college, it didn’t matter that the two men were the same height: about six-foot-nothing. Lue harassed Young for his diminutive stature. “He was just one of those guys,” says Young. “Even though he was small, he would talk trash and say, ‘You’re too little. You’re not strong enough.’ I’m like, ‘Dude, I’m the same size as you!’ ”

No surprise: Muhammad Ali always found a way, too. Before big fights, he and Bundini would even hold informal brainstorming sessions during training camp to chart their trash-talk course. The goal was to come up with disparaging nicknames for opponents and otherwise decide on lines of attack. The men understood their verbal assaults could do more than control public narrative; they could be a vehicle for competitive mind games, too. Against George Foreman, for instance, who was seen as a heavy favorite against Ali, they attacked his strength—his thundering punches—by dubbing him the Mummy. It was a caricature meant to make Foreman self-conscious about his plodding fighting style. But that wasn’t the end of it. Even on the plane ride to Africa, before the Rumble in the Jungle, Ali was practicing his trash talk. When told that calling Foreman an Uncle Tom wouldn’t have the same resonance in Zaire as it did in the United States, he asked, “Who do these people hate?”

He was told, “The Belgians.”

(The country had been a Belgian colony.)

Shortly after landing, Ali stepped in front of the cameras and announced, “George Foreman is a Belgian!”

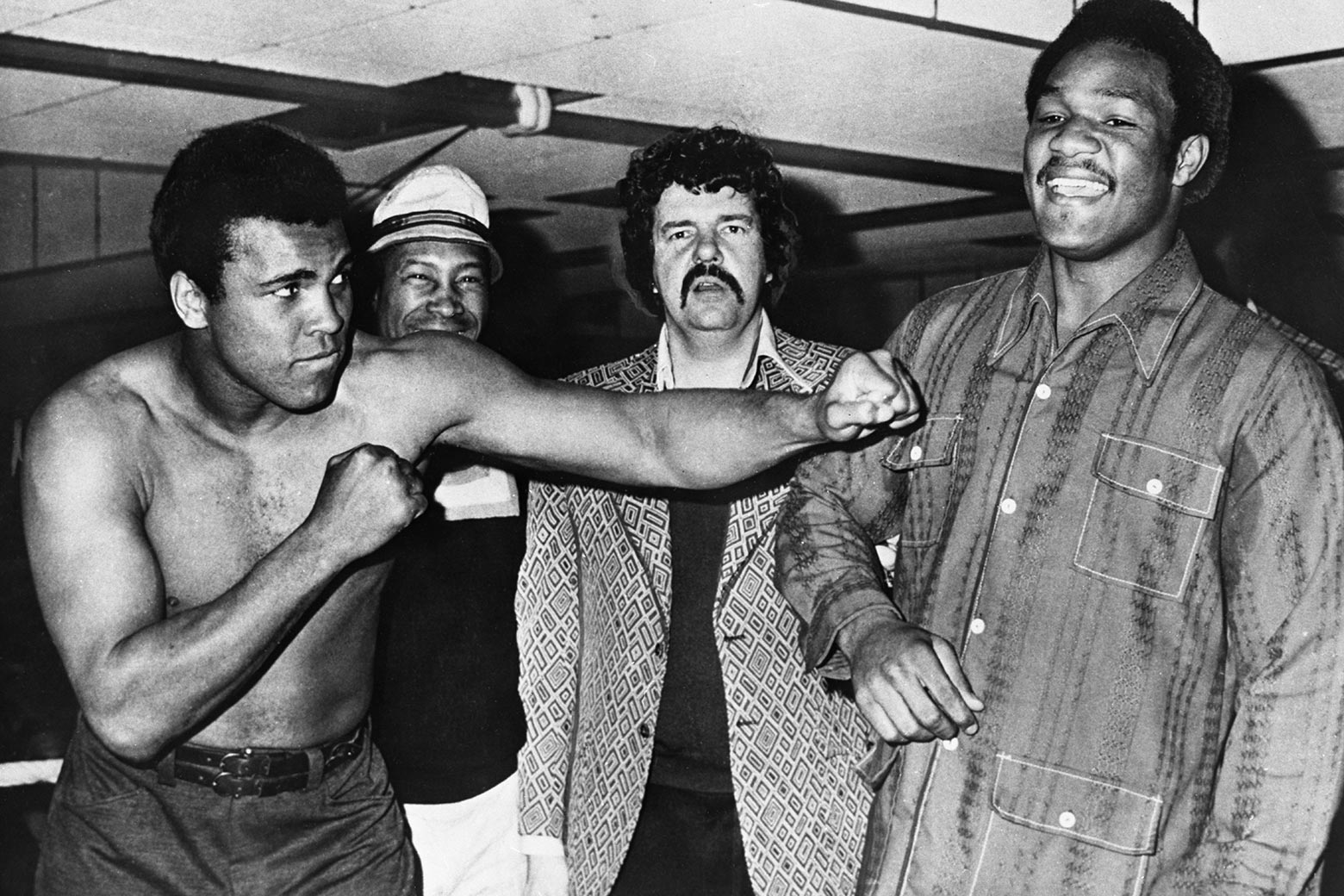

An even more perfect metaphor for Ali’s promotional and rhetorical mastery—for his ability to direct the extracurricular discourse and force opponents to accept his terms of engagement—would come at the end of a 1975 press conference before Ali and Frazier’s third and final bout, the Thrilla in Manilla. With the electrified promoter Don King looming just over their shoulders, the two fighters pose together for press photos. There’s something meta about the scene. “Look mean,” Ali says, contorting his face into an exaggerated scowl. At his side, Bundini chants, “He don’t have the look. He don’t have the look.” Frazier seems to chuckle. But then, as if suddenly levitating, Ali rises a few inches off the ground.

It’s no magic trick. Ali is up on his tiptoes.

The flashbulbs pop.

“Come on down. You ain’t that big,” says Frazier.

“That’s the way I’m going to look the night you meet me,” Ali replies.

Meta or not, the moment is no joke for Frazier, and it seems to stretch in his mind, as he surely hears the camera shutters click. Once again, Ali is forcing Frazier to play his game—or to look for all the world like the much shorter man. Frazier repeats himself, “Come on down.” But his pleas are futile. There’s no choice but to participate.

Frazier goes up on his tiptoes, too.