In January, Condé Nast announced that it was folding Pitchfork into GQ, laying off much of the staff of the influential, independent-minded music publication. The outcry was immediate. Why was one album-review website, founded nearly three decades ago in a suburban Minnesota bedroom, loved by so many music fans—and hated by so many others? Pitchfork transformed indie rock, but did pop transform Pitchfork? And does the Condé news really mean that Pitchfork is dead?

Over the past two months, Slate spoke to more than 30 Pitchfork writers, editors, and executives, past and present—as well as critics, industry luminaries, and some of the musicians whose careers Pitchfork made and destroyed—to tell the story behind the raves, the pans, the festivals, the fights, the indie spirit, the corporate takeover, and, of course, the scores. This is the complete oral history of Pitchfork.

1996–2000

“I’m in a Laundry Room, Man”

Ryan Schreiber (Pitchfork founder and CEO, 1996–2019): It started in my bedroom. I had just graduated from high school and was living at home. This was in a little town called Victoria, Minnesota, about 5 miles down the road from Prince’s studio, Paisley Park. I’d been reading tons of music magazines and was obsessed with music and music journalism. A friend of mine, he was super tech savvy, he introduced me to the web. I would go over to his place and he’d pull up the internet. He’d prompt me for search queries, and I started rattling off every band I could think of.

Brian Howe (contributor, 2003–23): The internet was this emerging uncharted frontier. It seemed natural that people were going to look for places to congregate on it. But someone has to make a bonfire for it all to come together.

Adam Krefman (director of business development and festivals, 2015–21): The internet was just a completely different place. It was almost like a solar system with large amounts of space between planetary bodies.

Schreiber: Those searches would bring back fan sites dedicated to specific artists, but I thought, There’s no reason this can’t be a music magazine.

—Ryan Schreiber’s 8.2 review of the Amps’ Pacer, the first review on what would become Pitchfork, 1996Kim Deal set out to record a different kind of record and came out with one that’s so terrific, it won’t leave my discman for at least three days. Well, that’s kind of a long time, I guess.

Howe: Pitchfork was made by people who had grown up idolizing legacy magazines. They had the impulse to dethrone them, while also wanting to emulate them.

Schreiber: I never reached out to any of the publications that I read. I thought they’d never accept me. From Day 1, I was like, If I’m going to do this, I’m going to do it for me and this community of writers and contributors. Let’s make our own thing.

Al Shipley (contributor, 2000): Back then, everyone was just buying magazines if they cared about music. Anytime you saw something covering more than just the big eight albums that Rolling Stone reviewed in an issue was cool.

Brent DiCrescenzo (contributor, 1998–2006): I found an interview Ryan did with the Revs. It might’ve been pre-Pitchfork. I want to say the site was called Turntable.

Schreiber: I got a cease-and-desist letter from another digital media company that had trademarked the name Turntable for a CD-ROM magazine, during that ultra-brief period in the mid-’90s when that was a thing. Ironically, we both wanted this very analog name that made no real sense for either of us. So, for about a month, I tried to think of a new name, but nothing fitting was coming to mind. Then I watched Scarface, and in one of the first scenes, Tony Montana is being interrogated by customs officials, and they notice this prison tat on his forearm. It’s a pitchfork, and a cop goes, “It means ‘assassin.’ ” That locked it up for me.

Chris Kaskie (president and co-owner, 2004–17): At the time, Pitchfork was clearly just one dude’s thing, even though Ryan had a lot of people contributing to it.

DiCrescenzo: I just reached out to Ryan and was like, “Hey, I’m writing reviews. You’re kind of doing the same thing.” I still have the first CD he sent me, which is Pave the Rocket, a band no one will remember. And yeah, I just wrote some shit, then started to talk to him on the phone. He was working out of his girlfriend’s parents’ laundry room or something. He was like, “Yeah, I’m in a laundry room, man.”

Schreiber: There was no way to get the contact information for anybody online. I had to call the public library, and they would start searching for what I wanted. I’d be sitting on hold for 45 minutes, then finally the clerk would come back with the address for, like, Matador Records.

DiCrescenzo: I don’t think that Ryan and I ever thought of ourselves as indie dudes. Because when I first met Ryan, his favorite artist was Tori Amos. In high school, my favorite band was Primus. So it wasn’t like we were ride-or-die.

Schreiber: We were early enough that our SEO was really strong. If you searched for these bands we were covering, there would be nothing online yet. We got a lot of traffic from that.

Mark Richardson (contributor, 1998–2023; managing editor, 2007–11; editor in chief, 2011–15; executive editor, 2015–18): Before Google, there was no surefire way to find anything about anything. But I followed a link to a Luna interview on Pitchfork.

Howe: When I got online looking for information about indie labels and this whole other world of music, Pitchfork was what you found.

Shipley: I started reading the site in 1998, when I was in high school. I was looking up some obscure album, and Pitchfork had a review for it. I was like, Oh, these guys have reviews every day.

Amy Phillips (news director, 2005–19; managing editor, 2019–23; executive editor, 2023–24): What made Pitchfork stick is that it was consistent. There was always something new on the site.

Eric Harvey (contributor, 2007–23): It was five reviews every day, 25 reviews a week. They were vastly outpacing Rolling Stone and Spin.

Schreiber: We probably had 1,000 reviews published by 1999.

Harvey: One of my students was an indie rock fan. One day, he was in my office hours and said, “Have you ever heard of this site called Pitchfork?” I [finger quotes] “bookmarked it” to my “RSS feed.” Another student had introduced me to peer-to-peer file sharing.

Richardson: I always felt that was a really overlooked part of Pitchfork’s rise.

Harvey: You’re reading about an album, and you’re literally downloading it to your hard drive and listening to it at the same time.

Richardson: Historically, it took a lot of time to become immersed in a music scene. It took resources. It took money. And even if you might trade tapes with your friends, it took 90 minutes to make a 90-minute tape. With file sharing, the immediate consumption, and the idea of a daily-updating website, you can follow along with what’s happening.

Jayson Greene (contributing editor, 2008–present): I was a person who worked at a radio station. I was like a caricature of the character from the Nick Hornby book High Fidelity. It was clear to me that these were my people, love them or hate them, and that I had found a place that I would go whenever I didn’t know what else to do and wanted to visit a website.

Richardson: I spent a lot of time on a message board called I Love Music, and I noticed early on just how much ire Pitchfork inspired. It felt like having an opinion on one of Pitchfork’s opinions was an important part of keeping track of what was going on in music.

David Drake (contributor, 2008–17): Pitchfork seemed to often have an attitude or an affect or a sense of humor to which you could react like, This guy thinks he’s cooler than me, and also, Is this guy cooler than me?

Cat Zhang (associate editor, 2019–23): I think a lot of women who worked for Pitchfork generally have a less zealous history with the site than a lot of the men who worked for the site did.

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd (contributor, 2003–07 and 2016–present): My boyfriend was really into Pitchfork. I didn’t read it all the time, because they were doing a lot of stuff that I wasn’t that into.

Schreiber: I was definitely looking at this new decade ahead and going, Man, we’re going to need a whole new canon. And I felt like that was on Pitchfork’s shoulders.

Carl Wilson (Slate music critic): When I started reading it, my main impression was that it was pretty juvenile.

Howe: It was made by a lot of really young, really immature men.

Greene: Those early years were what they were on purpose. It was a bunch of people writing to entertain each other and being somewhat delighted when they finally provoked a reaction from random strangers.

Shipley: They were one of the only places that would say, “We’ll cover anything.” Sometimes that would blow up in their faces. But still, there was a spirit of “anything goes.”

Schreiber: “If it’s not going to be sparkling copy, let’s just make it ridiculous and outlandish. Have a great time with it.”

David Turner (contributor, 2012–17): Everything from before 2001 is kind of dog shit. Those reviews are just bad. But that’s fine.

Shipley: There are things that were genuinely embarrassing that people now pass around as a party favor. You ever see the John Coltrane review?

—Ryan Schreiber’s 8.5 review of John Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard: The Master Takes, 1998’Trane takes it to heaven and back with some style, man. Some richness, daddy. It’s a sad thing his life was cut short by them jaws o’ death.

Shit, cat. It don’t make a difference.

Shipley: It makes sense that they eventually deleted a lot of the early stuff.

Howe: This stuff was all being written by boys who were into David Foster Wallace. I was obsessed with Infinite Jest in my 20s. I literally read it all the way through three or four times, probably.

Richardson: There was definitely a trend towards absurdity in some of the literature at the time. Another inspiration was an author named Mark Leyner. He was someone that Brent DiCrescenzo liked a lot.

DiCrescenzo: Mark Leyner has this weird hyper-ego first-person voice, this obviously comical, inflated sense of self that was so over the top that of course it’s not real. I just thought it was funny to be sitting in my childhood bedroom, writing, “I’m stepping off a private jet …”

Shipley: Brent was one of the big personalities at the site.

Schreiber: DiCrescenzo’s pieces were really divisive, understandably, because they were so conceptual. He would go really off the rails.

—Brent DiCrescenzo’s 1.6 review of Steely Dan’s Two Against Nature, 2000So, you pony-tailed Jeep-drivers and terrier-walkers, I’m crawling inside your minds like “Reeling in the Years” did so many decades ago. … I know that this review might hurt your feelings. Here, play with this shiny silver Nokia while I chat with somebody else.

DiCrescenzo: The bulk of music reviews are just unbearable to me. I was just trying to take the piss out of or lighten the mood and be like, This doesn’t need to be serious. I think, when people look back, they’re like, Well, these guys were bad journalists. It’s like, Well, we weren’t trying to be. I was just trying to write something funny.

Richardson: His reviews got a lot of attention. Anybody would say he was the star writer of early Pitchfork.

DiCrescenzo: I remember dissing Rammstein and someone sent a letter to my house that just said, “Your God is dead.”

Schreiber: Brent and I were probably more in contact about everything than most of the other writers, especially because we moved to Chicago at the same time. We used to hang out every day. And in 2000, we were on Napster as Kid A was leaking in real time.

DiCrescenzo: I definitely recall sitting there in my apartment with the futon, probably watching the video channel that had Juvenile and the Hot Boys on. You would download a song and it would take 45 minutes. You see that bar filling, filling, filling. You’re like, Come on, come on, come on and then like, OK, bam, I got Track 4! And then you would play that track over and over and over and over and over. And then you get “Treefingers.” You’re like, Wait, what the fuck is this?

Schreiber: We agreed from pretty early on that it was going to be a 10. He wanted to write a review that was going to be sort of as ambitious as the album—his version of the album.

DiCrescenzo: I always wrote with the music in my headphones. And I know this is going to sound so pretentious, but I was trying to write in a way that, as a reader, you would somehow feel how I felt listening to it.

Schreiber: It was really late. I’m just hounding him for it. “Where the fuck is this review?” And he’s like, “I’m just tweaking it. I’m getting it right.” So, probably around an hour later, this thing arrives in my inbox. He logs on to Instant Messenger and is like, “Don’t change a word.”

—Brent DiCrescenzo’s 10.0 review of Radiohead’s Kid A, 2000The experience and emotions tied to listening to Kid A are like witnessing the stillborn birth of a child while simultaneously having the opportunity to see her play in the afterlife on Imax. It’s an album of sparking paradox. It’s cacophonous yet tranquil, experimental yet familiar, foreign yet womb-like, spacious yet visceral, textured yet vaporous, awakening yet dreamlike, infinite yet 48 minutes.

Schreiber: I was editing it really heavily for a while, and at a certain point I stopped. Even though I had qualms with the review, I also knew that it was going to definitely get us all kinds of attention.

Shipley: The review was so ridiculous. Like, yeah, a British band with guitars did some electronic stuff. This is not actually something completely never-done-before. This is Achtung Baby.

Shipley: That was Ryan.

Schreiber: A lot of people who logged on to Pitchfork that day were seeing the site for the very first time. A lot of them also were young enough to just feel like, Hey, these are my peers writing about music.

DiCrescenzo: I don’t remember the exact numbers. I remember our normal reviews were probably in the thousands. Five thousand or something like that. And then it was like, Holy shit, we got into the tens of thousands, and then it was the hundreds of thousands.

Schreiber: Kid A was the first record where we were like, OK, it’s 2000—we’ve been doing this for a couple years as goofballs. Now we’re really ready to step it up.

2001–06

“The Pitchfork Effect”

Chris Kaskie: I was working for the Onion in the early 2000s. I read Pitchfork, I liked Pitchfork, but I was frustrated by the lack of consistency. Ryan needed someone to apply skills he didn’t have, whether it be business or advertising. I’m like, I’m just going to hit this dude up. This could be an actual magazine.

Ryan Schreiber: Chris could literally be called a co-founder of Pitchfork, even though he came on seven years into the site’s history. He registered the trademarks and turned us into an actual business.

Kaskie: It wasn’t incorporated. We set up payroll and set up health insurance. There’s checks that people weren’t getting paid. We had to go into Ryan’s email to see if anyone had ever written to him interested in learning about Pitchfork. I think the New York Observer was the first place to hit us back.

Hillary Frey (Slate editor in chief; author of that 2004 Observer story about Pitchfork): My central question was: Who are these unknown dudes in Chicago telling us in New York what’s good and bad in indie music?

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd: As I recall, there were only a couple other women writing there at that time, one of whom was Amanda Petrusich.

Frey: Their earnestness and wide-eyedness was pretty winning, as was their dumpy basement workspace. It wasn’t just that they were green, but they were true disrupters who had no idea what they were disrupting. It was both infuriating and inspiring that they were having an impact without setting out with that intention.

Schreiber: The readership was spiking like crazy, beyond anything I ever anticipated. Pitchfork was starting to turn into a business.

Brian Howe: Scott Plagenhoef was the first professional editor brought in to Pitchfork, and really changed things for the better in a lot of ways.

Scott Plagenhoef (editor in chief, 2004–11): I had a job in sports journalism in Evanston. I was friends with Brent, and I’m sure he introduced me to Ryan. I started getting into his ear about records and eventually started to contribute freelance copy editing, usually preparing reviews that would be published the next day. At the end of 2004, Ryan first hired Kaskie to operationalize and professionalize the business side of things. A month later, he brought me in to do the same to the editorial side.

Shepherd: Scott was a really good editor—I think he signified the professionalization of Pitchfork, because I got real edits back.

Howe: God, I imagine now what it was like for the poor guy managing this cattle pen of a bunch of slightly younger writers.

Amy Phillips: The office was, like, three small rooms. It kind of looked like a film noir detective agency.

Kaskie: Like a private investigator’s office in Logan Square.

Phillips: I was the fifth employee there. Schreiber called me, out of the blue, and was like, “Hey, do you want to be our news editor and move to Chicago?” I was 23, about to be 24.

Kaskie: It was me, Amy, and maybe two or three other editorial people.

Phillips: I remember having my first employee review in a closet.

Kaskie: We used to call that closet Burger Town. The office was right above this diner called Johnny’s Grill. It smelled like burger grease. It was gross. I’m pretty sure the ventilation was right behind the wall.

Phillips: The office was just chock-full of records, promo CDs stacked up to the ceilings, and posters and everything. I just felt like I was living, and breathing, music everywhere.

Howe: The news section was nothing like what it is now. There weren’t any reporters. I think it was an unpaid position. We basically just rewrote stories from NME but with jokes in them.

Phillips: There wasn’t a churn of places to get information, so it was very laid-back. You got your four stories up on Friday and took the rest of the day off and didn’t think about it till Monday.

Howe: The Strokes had gone on tour in Europe and they’d taken a piss in a river behind a stage, but it was some kind of really holy or sacred river. And it caused this big uproar. I can’t remember the details. This could probably be looked up. So, I did a whole “The Strokes: ‘Monumental Desecration’ Tour” post with the band defacing all these monuments all over Europe. That was kind of the temper of Pitchfork news at the time.

Plagenhoef: When I was hired, there was no publishing platform.

Phillips: Building those stories took a really long time.

Plagenhoef: I would wake up early every morning and copy and paste reviews and news items into the HTML code of the site in order to update it.

Tom Breihan (contributor, 2004–11): We all had big opinions. We all liked making fun of each other, and we all liked drinking. I remember that as being a great time, even though nobody was making any money. And I’m sure the site was exploiting all of us, to one extent or another.

Brent DiCrescenzo: Scott, Kaskie, Ryan, and I met in a diner in Logan Square in 2004. I was like, “This is bullshit. I know that my reviews are what’s driving most of the traffic to the site. You either give me money for my reviews or take them off the website.” So I technically sold them the reviews. Probably for not nearly what I should have charged them. But I was struggling to make rent. I needed fucking money. I had put in six years of daily labor on it. For Ryan, it was his entire life and being. But for all the rest of us, it was just a side hustle—or not even a hustle, just a hobby. It was a way to hang out with people and get CDs and meet some awesome people.

Kaskie: We needed to build a semblance of a plan to make sure every writer that writes for us is getting paid, at minimum. Whether or not that’s fair pay, we have to figure that out next.

Breihan: When I started freelancing in 2004, they didn’t pay critics.

Shepherd: I did get paid, but not at first, though. I was doing it out of the kindness of my heart.

David Moore (contributor, 2004–05): You had to write for free for six months before you could get on the payroll. The way it worked was you came on as a reviewer in a preliminary role, and you had to write five reviews that didn’t suck.

Plagenhoef: It was important to establish that writers weren’t going to chase us for payments, and we weren’t requiring them to invoice us, which was possible because everyone was paid the same for the same work.

David Turner: The first review I did got me paid $65. It took me four months to get paid. I had to bother multiple editors.

Andrew Nosnitsky (contributor, 2012–18): Pitchfork is one of the few publications I can say this about: I never had a problem with getting them to pay me.

David Drake: The reviews were somewhere in the area of $110 to $125.

Howe: The number that comes to my head is $50.

Shepherd: It wasn’t much, like $15. I wrote one track review and got a check for $2.50. I felt like it was more effort to walk to my bank than to just pin it on my fucking bulletin board.

Eric Harvey: I want to say, when I started, an A-block review was maybe $100, maybe $150. I might be overstating that. It wasn’t a lot. And then I think it was $50 or $75 for the lower-tier ones.

Shepherd: They didn’t have money for a long time. It must have been just ad revenue, and it was probably, like, Kaskie going directly to the Thrill Jockey offices and having them spend $350 on display ads.

Kaskie: We were charging $30 for two banner ads. It’s like, Oh my God, we’re going nowhere, man.

Drake: In college in the early 2000s, I remember meeting a guy who seemed like the kind of guy who would read Pitchfork. I was like, “Do you read Pitchfork?” and he was like, “Yeah.” That was Pitchfork becoming real to me.

Harvey: For my money, Arcade Fire was the one that sent it over the edge.

Turner: Pitchfork was a very different site post–Arcade Fire.

Moore: After one month of writing there, I got this huge review mostly because things were not super professional yet. I was like, “Hey, is anybody reviewing this Arcade Fire album? I really like it.” And Ryan was like, “Well, I kind of want to write about it, but I don’t think I have time, so yeah, you should definitely do it.” Then the deadline got pushed up—they wanted to get it out before the album release. I was 20 and I wrote this crazy review. I suggested giving this thing a 10, and a lot of people were against it because it was actually a divisive record on the staff message board.

—David Moore’s 9.7 review of Arcade Fire’s Funeral, 2004So long as we’re unable or unwilling to fully recognize the healing aspect of embracing honest emotion in popular music, we will always approach the sincerity of an album like Funeral from a clinical distance. Still, that it’s so easy to embrace this album’s operatic proclamation of love and redemption speaks to the scope of The Arcade Fire’s vision.

Harvey: There’s a venue in Louisville called the Southgate House. I saw Arcade Fire there, I want to say, early 2005. The place was packed, and there was an absolute explosion of noise when the band hit the stage—the kind of thing you’d expect for a legacy act with a devoted fan base, not a band that no one had heard of two months prior. I was like, Oh, OK, this is the effect that Pitchfork is having.

—“The Pitchfork Effect,” Wired, Sept. 1, 2006“Putting too much weight in somebody else’s opinion of a piece of art, that is a dangerous thing,” says Richard Reed Parry, a musician for Arcade Fire, whose album Funeral received a rapturous 9.7 rating from the site.

Jeff Weiss (contributor, 2011–17): The Arcade Fire review obviously changed everything. I remember, six months later, the L.A. Times did a big story on the site, and they had kind of arrived.

—“The Zeitgeist Guys,” L.A. Times, March 7, 2005Shortly after a glowing Pitchfork review came out in September, the Arcade Fire’s label, Merge Records, was hounded by nearly two dozen publications asking for copies of the album. “I said, ‘Sure, but didn’t I send you a copy two months ago?’ ” said Martin Hall, a promoter for Merge.

Schreiber: Once I got a taste for it, I was like, Man, I can’t believe we can do this.

Howe: I think of a puppy that’s just pounced on a grasshopper for the first time and is like, Oh, I can do that. Let’s try and do that again. Let’s try and do it on purpose this time.

Harvey: Clap Your Hands Say Yeah’s album from 2005 was another big Pitchfork moment when Pitchfork coordinated this band that came from the blogs.

Howe: I genuinely was enthusiastic about that band. But the message I took from whatever Ryan said to me was, like, “Yeah, we’re going to blow this band up. Do you want to be the guy?”

Schreiber: Clap Your Hands, in hindsight, maybe not the most—how would I say this? Probably not our finest draft pick.

Megan Jasper (CEO of Sub Pop Records): They knew music really well. They could make connections in a lot of the reviews that may have been lost on a lot of other people. And oftentimes you could take those connections and actually discover something else. Pitchfork really did truly serve as a music discovery resource for a lot of people. And it was trusted, because they had great writers and they had great thinkers.

Puja Patel (contributor, 2013; editor in chief, 2018–24): Reading Pitchfork was kind of like talking to the guy at the record store. It was the person who was a little arrogant—but possibly rightfully so.

Kaskie: We are not trying to be everything to everybody. We’re trying to be something to someone.

Patel: In many ways, I’ve got to say, I didn’t necessarily think Pitchfork was intended to be for me. But at the same time, I desperately wanted to know what they thought about things.

Jasper: As a publicist, you’re pitching multiple publications for a review or a story or a cover, but really, there was a massive window where if you were able to land something positive from Pitchfork, it was the most impactful. We would see immediate spikes on all of the records that were favorably reviewed, and we would see a really loud nothing on any new records that were just completely fucking decimated.

Zola Jesus (musician, 2017 Best New Music recipient): It felt like Pitchfork was in control of the destiny of my career to an extent, because it did have this huge place in breaking or burying artists. The pressure as a musician got more to be I better get a good review.

Daniel Gill (owner of Force Field PR & Mgmt): That’s what caused people to put so much weight in their reviews—they were not scared to call out somebody when they turned in a stinker.

Kaskie: In order to know what’s good, you have to know what’s bad. So negative reviews were important.

Jasper: You loved the great reviews when they would do right by an artist, and you hated the super snarky, shitty reviews.

Mark Richardson: We talk about all of the stunt reviews that Pitchfork had, a lot of which are very funny and I thought were great.

Kaskie: I never “wrote” any more than a few reviews on the site. But one of them was the video of the monkey peeing in his own mouth for the Jet record Shine On. We were sitting at Lula Cafe, right downstairs from the Chicago office, and we’re like, “This record’s dog shit. I just got this video from my friend, let’s just put this up instead.” We used the byline “Ray Suzuki,” our catchall byline for a writer who didn’t want to use their name directly. And it was as simple as that. We laughed and we did it.

2007–15

“Sorry :-/”

Craig Jenkins (New York magazine music critic; Pitchfork contributor, 2013–16): I thought the site needed a turnaround. The perspective was very walled-in. It was antagonistic toward the stuff that the average person would be appreciating.

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd: When Pitchfork started to get much bigger, the emails I was getting didn’t really reflect who I wanted to be writing for. Most of it was invective, and it was all, like, young white men who were writing from college email addresses. I remember I wrote a column about some split 7-inch that Erase Errata and Sonic Youth had done about Mariah Carey. I said something like, Mariah’s album is fine, which is insane, because that album was fucking amazing. But people were fucking furious that I mentioned a pop star. It bummed me out a lot.

Scott Plagenhoef: One of the immediate editorial takeaways I had was that Pitchfork risked being a dead end if it didn’t diversify what it covered.

Tom Breihan: It was fundamentally obvious that Cam’ron was more interesting than Modest Mouse or whatever.

Andrew Nosnitsky: I don’t think indie rock was the defining music of my generation. I think quite transparently it was hip-hop, but for purely mechanical and straight-up white-supremacy reasons, Pitchfork is seen as the defining music publication.

Lindsay Zoladz (New York Times pop music critic; Pitchfork associate editor, 2011–14): The first Lorde album is a rare one where I think readers can tell you wrote something to a higher score than it ended up getting. It received a 7.3, but I probably wrote an 8.1, and I think history has proven me right. The funny thing, though, is that review ended up running in the C-slot that day, behind, like, the Afghan Whigs or something. We ran a review of the Lorde album a week late, and in a C-slot, as though it were not important, but some of us felt like it was a triumph just to get it reviewed at all.

Dan Le Sac (musician): Pitchfork could be a little … I don’t want to use the word pretentious, but it seemed to form a scene around a band instead of just letting a band be.

Ryan Schreiber: We wanted to create a roster of artists who people found out about through Pitchfork, who became associated with Pitchfork. It became a little bit of an industry unto itself.

Daniel Gill: I think they had the approach of, We’ll find a group of maybe 20 artists and just kind of report on everything they do.

Amy Phillips: These were the people we cared about so deeply, and we knew our audience cared. We can decide that Jeff Tweedy getting into a fight with a drummer onstage is, like, the biggest story in the world.

Bethany Cosentino (frontwoman of Best Coast): They wrote about everything I did. My friends used to joke, “You could take a shit and Pitchfork would write about it.”

Chris Kaskie: You could see the impact. 2005 is our first Pitchfork Music Festival, then 2006 it keeps going. We start to see these bands playing in front of audiences 10 times the size of their biggest show ever. That’s the goal, man. To put fucking Titus Andronicus in front of 10,000 people. They have never done that before. Then we’re headlining the Silver Jews with 25,000 people. That is fucking amazing.

Gill: In those early years, we usually have six or seven artists on the Pitchfork Festival bill every year, and I would have people doing simultaneous interviews with six different artists and just moving everybody around the room. Nardwuar is doing the interview over here, WBEZ is doing the interview over there. Woods are over here, Vivian Girls are over here. It was pretty wild.

Plagenhoef: The Pitchfork Festival proved you could sell out an experience with artists who wouldn’t normally be considered headliners.

R.J. Bentler (vice president of video programming, 2007–19): We built the first Pitchfork.tv site on a Flash player from scratch. Somehow Radiohead caught wind of what we were doing, and we launched with this incredible Radiohead video of Thom Yorke playing drums. We went along for a few years there doing our thing, and YouTube was obviously growing immensely, and we went out to L.A. and managed to convince them to give us a few million dollars to start a YouTube channel.

Megan Jasper: It became normal, honestly, for some bands to grow and be able to sell 100,000 records. Indie rock just kept blooming and growing. It became something larger than we had ever anticipated.

Carl Wilson: There was this frenzy going on about band discovery at the time in a way that I have never really seen in North American music journalism before. It reminds me of what the ecosystem was always like in the British music-weekly world. They were basically all covering London and vying with each other to be the one who discovered the latest thing in London. The result was that things got a little polarized. Bands were either vying to be the next big discovered band, or they were setting themselves up in opposition to that and trying to make music that nobody could market in that way.

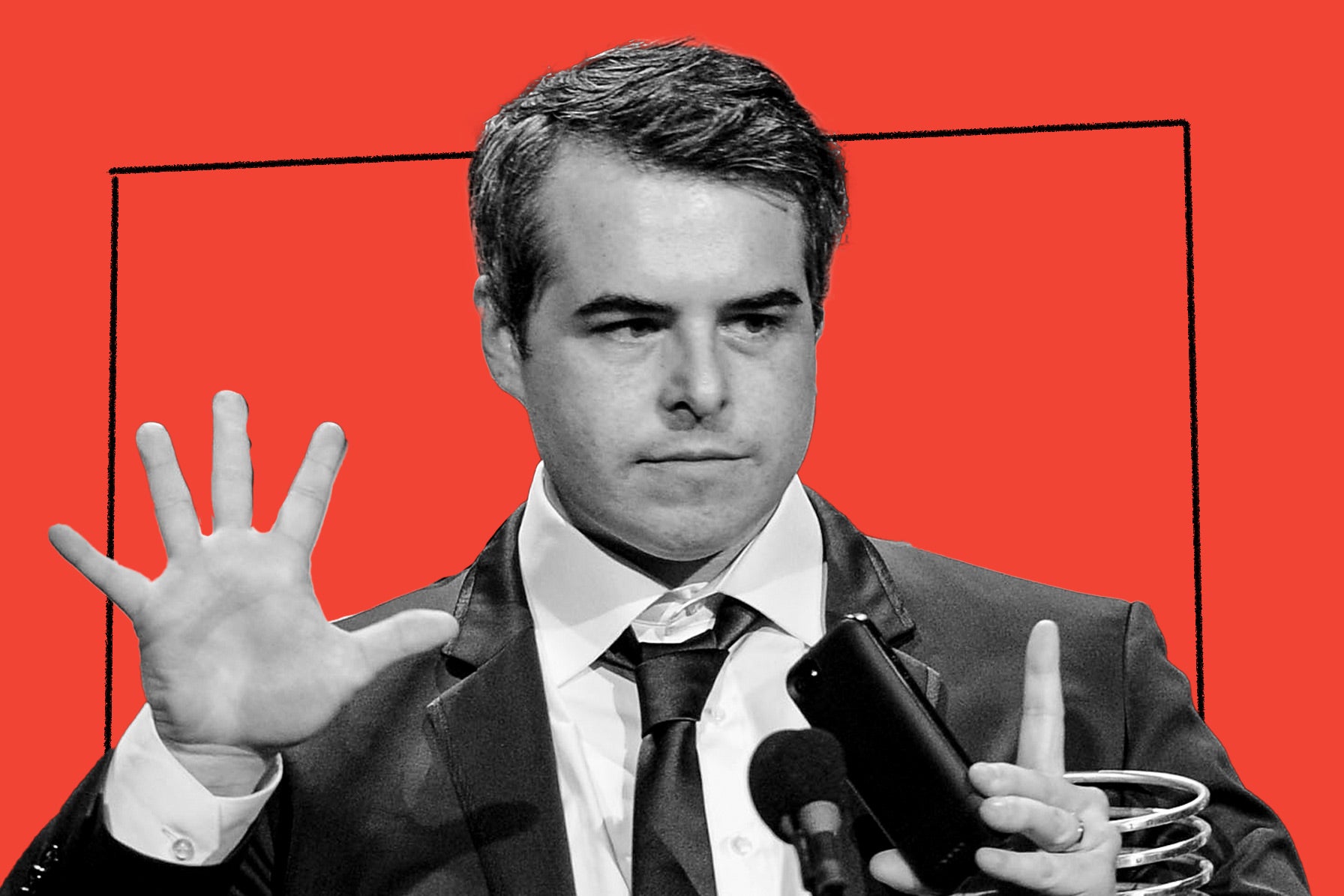

Mark Richardson: Pitchfork became very aware of its power. For that couple-year period after Arcade Fire, the awareness of that was probably detrimental to Pitchfork in some ways. That self-consciousness about where Pitchfork fit into things and the power that it had kind of informed how you would hear music. And the famous example would be Black Kids.

Kaskie: We went a little overboard on their EP.

—Marc Hogan’s 8.3 review of Black Kids’ Wizard of Ahhhs EP, 2007You can download Black Kids’ four-song demo, Wizard of Ahhhs, for free on their MySpace—it’s not available in stores. They’re giving away something we can’t buy often enough: a record with not just a distinctive aesthetic, but also one single-worthy track after another.

Richardson: We had plenty of chances along the way to step back and say, “Is Black Kids really a great band?” We didn’t, we got swept up in it.

Plagenhoef: With Black Kids, it was an apology to really everyone involved—the audience, the band.

Richardson: Now we’re saying, “Oh, that was a mistake.” To me, that’s not the best of what I remember of Pitchfork.

Kaskie: Those are my dogs. I took the picture in my kitchen.

Richardson: I think Pitchfork got better after that in some ways because it wasn’t entering the mix so much. Once you’re like, “We say it’s great,” and it doesn’t necessarily become a huge deal, then it’s like, “Well, we better just focus on what we think is good then, because we don’t have the Midas touch of creating a frenzy.”

Plagenhoef: The closest I remember to allowing myself to feel like we really shifted something was before the 2008 festival. We did a standalone show in Millennium Park with a few bands, including Fleet Foxes. It was a gorgeous night, we’re sitting along the waterfront in the grass of a Frank Gehry–designed amphitheater listening to them performing “White Winter Hymnal,” a song we first heard maybe six months earlier on their MySpace page. Having a small part of bringing something like that to so many people felt magical.

Eric Harvey: We mostly interacted on what was called the staff board. It was a private message board, named Staffington. All the writers were on it.

Brian Howe: We’d get on the board and show off, and peacock our hot takes, and share whatever we called “memes” in those days.

Phillips: That was how I first “met” all of these people, through this message board.

Plagenhoef: It was a huge timesaver to have all of this dialogue written down and accessible. As far as our staff was concerned, Mark Pytlik discovered Beach House. He started a thread on the album, said, I know we get a lot of pitches from this PR company and you may not be inclined to check them all out but this one is special.

Breihan: It was the same type of shit that we would be talking on Twitter a few years later, except even more unguarded because it was just this small closed loop of people doing it.

Howe: Pitchfork was just a bunch of people spread out all over the country. A lot more staffers from the Midwest, people from the smaller scenes, and even people from the middle of nowhere. The message board was a place that made Pitchfork feel like a community and like a lifestyle.

Harvey: When an album got announced, Pitchfork would usually have a watermarked MP3 copy of it, and they would upload it to a password-protected FTP server. And so we would listen to it, and then we would talk about it on the staff board. Some records got six, seven, eight pages of conversation. Other records were a fart in the wind.

Howe: Joanna Newsom’s record Ys eventually leaked from that server.

Phillips: I think Drag City never forgave us. When the Condé Nast sale happened and we were doing the transition, one of the first things was, like, OK, we have to nuke this server.

Cat Zhang: Everyone who works at Pitchfork probably has a really ambivalent relationship with the score system and yet knows that the moment that Pitchfork abolishes it, the whole site tanks.

Schreiber: The ratings matter. We have 101 possible ratings, and it needs to mean something. Let’s really protect that.

Brent DiCrescenzo: We inherently understood how ridiculous and funny it is to split hairs between a 4.3 and a 4.4. It’s ridiculous. But we thought it was funny. And now it’s like, it seems so arrogant and serious.

—“Pitchfork Gives Music a 6.8,” the Onion, Sept. 10, 2007Schreiber’s semi-favorable review, which begins in earnest after a six-paragraph preamble comprising a long list of baroquely rendered, seemingly unrelated anecdotes peppered with obscure references, summarizes music as a “solid but uninspired effort.”

Lindsay Zoladz: I remember emails from Mark Richardson like, “This sounds like a 7.0, is that OK with you?” I would be like, “How about a 7.3.” I sometimes relished in pushing back on a score because I had a lot of fight in me at that age.

Jenkins: Past a certain decimal point, I never cared, which is a funny thing at a website where people are really fighting over a .2.

Howe: The way I read Pitchfork, and the way I think it should work anyway, is that the words represent the writer’s view, and the score represents the site’s editorial perspective.

Harvey: There were times where Scott would try to place a review with somebody who had a vibe on the album that synced up with the editorial vibe, which I always thought was fine. You want to have a strong editorial voice in this magazine.

Breihan: Every once in a while I would hear one of the other editors complaining about Schreiber’s tastes.

Matthew Perpetua (contributor, 2009–12): I think sometimes if Ryan just wasn’t feeling an album being Best New Music, he would have the prerogative to downgrade it. It’s like that. It’s his company.

Schreiber: There were definitely a lot of records throughout Pitchfork’s history where I either pulled back on the hype wagon, or other times where the staff wasn’t feeling something, and I was like, “This is something that is really going to resonate.” And in those cases, you’re just trying to steer the ship to the port as steadily as you can.

Breihan: I was once told that Ryan Schreiber was the reason Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago did not get Best New Music.

Schreiber: I did not see what was special about that album in the beginning.

Breihan: I went into Pitchfork with a chip on my shoulder, because I was like, “They never write about rap, and if they do, they write about it wrong.” It’s all Sage Francis. It’s no Three 6 Mafia.

Nosnitsky: It seemed like a lot of online music journalism was boosting backpack rap aggressively. Little Brother, Def Jux—which, I like a lot of that music, but I’m sure if you go look at Metacritic for what the best-reviewed 2003 rap albums are, it’s going to be all MF Doom and no 50 Cent.

Jenkins: This website could use a lot more people who are writing about street rap who understand anything about the inner city from experience, who can talk about that music, who can talk about the lives that the people are leading that make it.

Breihan: It was a very, very white, very male group. And not just that, but people from a particular musical perspective. You could advocate for David Banner if you could also talk about Devendra Banhart.

Timmhotep Aku (senior editor, 2018–19): Pitchfork felt like maybe an interloper at a certain point when it came to hip-hop, until they took steps to kind of legitimize itself with the right writers—being more cautious with tone and reverent to context.

Nosnitsky: What hit me quickly in writing for Pitchfork is suddenly I was not a person who had been writing about rap music for a decade at that point. I was an indie white guy on the indie white site, and anybody who wanted to catch feelings about it put me in the same crosshairs as everyone else.

Aku: I think a big blemish on Pitchfork’s legacy is taking Chief Keef to the shooting range.

Jenkins: That was definitely way up on the list of Pitchfork rap mishandlings.

David Turner: That was Vice-level shit.

—“Chief Keef Jailed After Judge Finds Probation Violation,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 15, 2013During the approximately two-hour hearing, a gun range employee testified that Chief Keef was holding the rifle during an on-camera interview by Pitchfork Media, an Internet-based music publication. The judge ruled that by holding the firearm, Chief Keef violated the terms of his 18-month probation sentence for pointing a gun at a Chicago police officer in 2011.

R.J. Bentler: I wasn’t there for that shoot. I don’t really remember the specifics of how that was concepted, but clearly, that was an oversight, a mistake. I don’t know what more I can really say about it.

Richardson: Gawker published a piece that was very funny. The headline was something like, “There are more people named Mark writing for Pitchfork than there are women writing for Pitchfork.” There were women that wrote for the site from the very beginning, but the idea that it was mostly white guys was totally true. That was really embarrassing. I became editor in chief in 2011, the year Pitchfork moved to Brooklyn. Things really started to change then.

Zoladz: I don’t know that I’d have a career without Mark. He DM’d me on Twitter and said, “Feel free to pitch me sometime.” I was 23 or 24, living in an attic apartment, and I went home from my job and I poured myself a very large glass of wine, to the brim, and I sat down and I wrote an email to Mark pitching all these crazy ideas that I had.

Turner: I was at my college library, I was working, and then I got an email from Mark Richardson. I felt so fucking giddy. My co-worker was like, “What’s going on?” I was trying to explain it, but he didn’t give a fuck.

Puja Patel: Mark was one of the first people from the site to reach out to me just to kind of say, “Hey, what’s up? I like you and your writing.”

Jill Mapes (senior editor and features editor, 2016–24): Mark Richardson is a mentor of mine and was a proponent of my work. I think Richardson’s era as EIC and part of Plagenhoef’s era was when it was getting more professional—they launched features, they were doing these incredible, dynamic-looking cover stories.

Zoladz: I was hired to work in an office in Williamsburg, and then we moved to an office in Greenpoint.

Jayson Greene: It was whitewashed, cinder block walls, literal bare lightbulbs.

Jeremy Gordon (deputy news editor, 2014–16): There was one bathroom that was shared with the floor, which in retrospect was so crazy. Two urinals and one stall for a whole floor.

Zoladz: It was really fun and I met some amazing friends there. It was a social thing too. That was a time when all the venues were still in Williamsburg. So I would finish my workday and then just walk to a show at 285 Kent or Death by Audio or Glasslands or something, all these places that don’t exist anymore.

Jenkins: In 2009, I went to a Williamsburg waterfront show where Grizzly Bear and Beach House played, and Beyoncé and Jay-Z attended. Those New York artists even being in the same room goes to show how blasted-open the barriers between indie rock and the mainstream were. These magical collisions of taste are, I think, uniquely Pitchfork.

Phillips: When Radiohead dropped In Rainbows, I just wrote this completely unhinged news story that was like “NEW RADIOHEAD ALBUM AAAAAAAHHH!!!” But the next time Radiohead dropped an album, it was very much like, “Radiohead announced a new album. It’s coming on this day.” We grew into a legitimate news enterprise.

—“Indie Music Site Pitchfork Wins National Magazine Award,” the Hollywood Reporter, May 3, 2013Among the winners at the American Society of Magazine Editors’ prestigious National Magazine Awards on Thursday night was indie music website Pitchfork, which picked up an Ellie (ASME’s elephant-shaped trophy) for General Excellence in Digital Media.

Schreiber: We were just trying to weather the state of the media at that point. We were well into the era of social media influencers sucking up all the marketing dollars and ad dollars. So we were making a decent go of it, but it was getting harder and harder.

Adam Krefman: I think the economic headwinds in small or niche media are really strong. And if you don’t have diversified revenue, and specifically if you don’t have a really good model to bring in basically a paywall of some kind or some type of membership model or something, it’s nearly impossible to make it on advertising dollars alone.

Schreiber: We needed to find a partner. Because otherwise, we were going to have to make some very difficult decisions.

Greene: I remember very clearly a huge advertiser blithely changed the nature of their reporting schedule and told us that we wouldn’t be getting the money that we always got for another 60 days. There were moments like that where you were such a tiny guppy that it was kind of hard to do anything except brace yourself.

Kaskie: I spent the entire year of 2014 going and meeting with different types of people that have money, whether it’s VCs or private equity or anything else. And most every time, the only thing they ever wanted was scale. And unnatural growth, non-organic growth is not what we do. The minute you do that, you’ve pissed in the fucking waterhole. It’s over.

2015–24

“A Very Passionate Audience of Millennial Males”

Al Shipley: Pitchfork basically did the classic indie rock thing of building a cool thing, selling it to a big company, and then the big company fucks it up.

Chris Kaskie: We started talking to Condé Nast, at first just about video syndication. And they asked if we’re open to an acquisition. So it’s like, “Yeah, let’s investigate that.”

Ryan Schreiber: We were really enthusiastic and very excited about it in the beginning, because it felt like, here is a place where great journalism is valued, is prized, and we’re now going to have resources to do that much more of it.

Mark Richardson: My immediate response was that if this is going to happen, this is probably the best version of it. At some point Vice had said something like, “What if we buy Pitchfork?” I knew that there had been conversations around that. I was like, “Oh, that would suck.”

Jayson Greene: If I’m going to be owned by a major media corporation, what’s the one that you want instead of being owned by the place that also owns Vogue and the New Yorker?

Schreiber: The pitch was that we could lean on them for resources to support new verticals like our print magazine, the Pitchfork Review, and film site, the Dissolve, while drawing on each other’s expertise to help pave the way forward.

Timmhotep Aku: I wasn’t one of those people who were like, “Oh, you’re selling out to the man.” You’re kind of all the man in different flavors. There’s a big corporate man, and there’s an independent man.

Jill Mapes: There was this assurance that things weren’t going to change and that they weren’t going to make us move into the World Trade Center. And then by that summer, we were moving into the WTC.

Amy Phillips: I think that so much good came out of that marriage. I mean, just strictly resource-wise. I got pregnant a year after the sale, and Condé Nast had a whole maternity plan, and they had a pumping room at the office. I don’t know what that would’ve looked like if we hadn’t been a part of Condé.

Richardson: Of course, the first day was a disaster.

—“Pitchfork Media Becomes Part of Conde Nast Stable,” New York Times, Oct. 13, 2015The acquisition will take immediate effect. It gives Condé Nast a stand-alone music publication with a strong editorial voice, said Fred Santarpia, the company’s chief digital officer, who led the acquisition. It brings “a very passionate audience of millennial males into our roster,” he said.

Richardson: That was kind of a worst-case scenario in terms of how it was messaged. The staff took that very hard and they were already pretty nervous about it.

Jeremy Gordon: They brought us into a meeting with Ryan and Fred Santarpia, the guy who gave the “millennial males” quote. There were trays of food. They made a Champagne toast, and I knew pretty much immediately that the site was going to change. I remember very dramatically borrowing a cigarette from my co-worker. I was like, “I need to go take a walk.”

Quinn Moreland (staff writer, 2015–22): When Condé bought Pitchfork, from what I understand, no one got any sort of pay bump. There wasn’t: Suddenly we have all this money, and everyone’s receiving it!

Gordon: We were all waiting, like, Are they going to give us more money? What is the gesture of goodwill here?

Moreland: This was my introduction to unionizing, in a way. It was what eventually flipped the lightbulb. We had a meeting at Charlotte Zoller’s house in Greenpoint. That was the first time it seemed that the editorial staff had gotten together to talk about: “Why aren’t we getting any benefits from this acquisition?”

Gordon: The attendance was pretty full. The word union wasn’t said out loud, but I was interested in what collective positions we could take to shore ourselves up. Everyone was on the same page emotionally, but we didn’t have the language to really organize.

Mapes: There’s a before-and-after for anybody who experienced Pitchfork pre-union and post-union.

Moreland: I had been making $32,000 a year. I think there is a lot of bitterness within that publication for all the years that people were working for crumbs and being treated like shit.

Schreiber: Pretty quickly after the sale, it turned into us fighting for resources and trying to help people understand what Pitchfork even was.

Kaskie: In January 2016, Ryan and I went to a Condé meeting. It was me, David Remnick, Scott Dadich from Wired, and so on. The CEO pointed to a board and was like, “We’ve lost some money, here’s our goal for next year.” And I looked at David Remnick. I had just met him that day. I was just like, “OK, well, I don’t know how we’re going to help that.”

Schreiber: It became apparent pretty much immediately, when they laid out what the traffic goals were … well, how can I say this? I think our expectations were just different from what was delivered, and what was promised never really materialized.

Kaskie: It was very clear that the energy in the room shifted to, like, “Oh my God, we all have to figure out how to make more money.”

Schreiber: As we got deeper into the relationship, we were made to move into the World Trade Center, into the Condé offices, and given this whole initiation situation, we started to realize how little anyone there knew what Pitchfork was, and who its audience was, and its history.

Greene: I remember thinking that I felt like we were on a middle school field trip. It was a very funny and awkward situation, going to this gleaming spire of a building. We’d been working in this place with barely any plumbing.

Moreland: When we started at the World Trade Center, we had a finance team that sat next to us. A majority of the people just seemed like they didn’t care at all about the site.

Kaskie: For a while we had some of the most brilliant salespeople in the entire world at Pitchfork. Those people lived and breathed music. They knew more about the B-sides on Merge Records from 1993 than anyone in the world.

Richardson: Before you knew it, our sales guys were moving on, and now we’re dealing with Condé’s salespeople, who really didn’t understand the audience.

Kaskie: I broke my contract two years in. It literally said that I was responsible for Pitchfork, the brand, and all of its moving parts. And so any diminishment of that role meant that I have rights to terminate my agreement. And there were plenty of people that would be in there saying, “No, you can’t do that.” When you make it harder for me, you have diminished my ability to do my job.

—“Pitchfork Media Founder Ryan Schreiber Leaves Company,” Billboard, Jan. 8, 2019Speaking with Billboard, Schreiber, 42, says his decision to leave Pitchfork has been about a year in the making, and involved ensuring that he left the publication in good hands—both under Condé Nast, which acquired the company in 2015, and with new editor-and-chief Puja Patel, who has overseen all general operations since joining in September. … “I don’t want to be defined in my life by just one thing. I feel like, in a sense, I’ve kind of beat the game.”

Schreiber: To be real, also, at the same time, the result of Pitchfork signing on with Condé was that it did get to do another eight years of great music journalism that it might not have been able to do otherwise.

Moreland: I remember there was a contentious meeting when we wanted to go public with our unionization campaign. This must’ve been in 2019. There was a party for a Sky Ferreira cover story, the first under Puja. Condé was very excited about it. They had this party for it at Kinfolk. Anna Wintour was there. We had wanted to go public that day and make it a big, in-your-face, “There’s all this money being spent, but we’re not seeing any!”–type situation. I think, in retrospect, it was the right decision not to do that.

Puja Patel: I came in with a pretty strong vision of what I wanted to do, which was make things a little more accessible, make things more expansive, bring more women, bring more people of color into the fold, and also just kind of relax a little.

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd: I credit Puja with turning that place into something that was better, editorially, than it’s ever been.

Patel: I think what people don’t always realize is that simply having someone at the top who is of a background that is not traditional to the publication, it does not mean that the rest comes easy. If anything, it just means that there is more pressure, more eyes, more weight, more expectation. It takes a year of getting folks to trust you, to prove that you are doing the work of diversity intentionally and not in a way that is showboaty and tokenizing, but in a way that furthers the journalism.

Moreland: I remember the bargaining session that Puja came to. She spoke about her past at Gawker, being involved in organizing there and that it was something she found very important. I think she was supportive the whole time, but she also had to deal with Condé, who were clearly not supportive.

David Drake: She brought in a lot more writers of color and writers with different backgrounds. Stuff that I had felt kind of lonely in championing, like Jazmine Sullivan was now Best New Music.

Shepherd: She made Herculean efforts to diversify it in a way that was natural and not just ticking off some DEI boxes. I really appreciated that because especially in music criticism, a lot of women get out of the game when they hit middle age. And credit to those who are still doing it, because it’s not easy, especially when you have kids. But I really appreciate her for looking at a middle-aged woman and recognizing my writing on its merits rather than whether or not I can stay out past 11:30.

Patel: From what I’ve heard, the previous era, it was a pretty small room where things like Best New Music or big pans were decided, or what might get covered and get skipped. We have some of the best experts in their genres on our staff. So I really try to let those folks have a stronger hand in how things were scored within their expertise. If Alphonse Pierre is coming to you saying, “This young rapper is making the most interesting music in Michigan,” you should trust him.

Kieran Press-Reynolds (contributor, 2021–present): What’s honestly really nice about Pitchfork is that even though a lot of the staff were millennials and older, they were not the Bob Guccione Jr.s of the world. They were appreciative of being introduced to things.

David Turner: The idea that people have about Pitchfork, like, “Oh, it used to be about indie rock and it used to be serious, and then it got all interested in women and people of color,” never made any sense to me. Because it was on that trajectory.

Dean Van Nguyen (contributor, 2013–present): Since the early days when it was very much an indie-rock website, they went through a long-term development, and rap became one of the cornerstones. When they gave Justin Timberlake’s “My Love” song of the year, it was signaling that a lot of the more sophisticated pop was also coming into their view.

Cat Zhang: Sometimes people claim that you are part of this Pitchfork conspiracy to shift opinion to what’s popular, now that norms have changed. I’m like, “No, I’m just young, and I wasn’t paying attention to those guys at that time. I just like pop music.” I don’t really want to be beholden to what Ryan Schreiber had to say, and it’s frustrating as a young woman to have to account for the failures of these guys.

Greene: The idea that somehow this pop shift happened, and particularly in relation to being sold to Condé Nast, is hilarious.

Turner: Was the poptimist turn at Pitchfork when they put Big & Rich on their top songs of 2004?

Greene: I would ask anybody to look at the review slate of the past year and add up the number of experimental electronic records, records by noise artists or electronic collage artists, and then compare that to the number of records that were released by major labels, by pop stars. I just think it’s a stupid claim made by people who clearly didn’t read Pitchfork very much.

Gordon: All of a sudden we decided that we were going to cover bigger artists right after the sale. There’s nothing wrong about that, but when you open the door to that sort of growth, you can no longer decline coverage for reasons that are simple as “I don’t want to cover that shit.”

Moreland: At a certain point, Pitchfork couldn’t be a legitimate cultural voice without acknowledging mainstream music. That’s just, like, you’re lying to yourself. That’s a huge gap.

Zhang: It is true that especially as music media corporatizes and has to think about SEO, the more you have to run a review of the Taylor Swift re-recording. You have to write a news item about Taylor Swift. It doesn’t necessarily mean that we had to review her well—there was no mandate that was like, you had to give Taylor an 8.

—Jill Mapes’ 8.0 review of Taylor Swift’s Folklore, July 27, 2020There are those who already dislike Folklore on principle, who assume it’s another calculated attempt on Swift’s part to position her career as just so (how dare she); meanwhile, fans will hold it up as tangible proof that their leader can do just about anything (also a stretch).

Mapes: The review went up at 1 a.m. And about an hour later, I started getting phone calls and weird voicemails that weren’t even like … I could barely even hear what they were saying. It’s not like they were screaming at me. It was just like they had access to my phone number, so they just decided to see what would happen if they disrupted me in the middle of the night.

—“Taylor Swift Remains Silent as Fans Doxx and Harass Music Critic Over ‘Folklore’ Review,” Daily Beast, July 30, 2020Various tweets, some of which have now been deleted or removed and some of which still remain, included Mapes’ address and phone numbers old and current. Some have included photos of Mapes and even her home. Users have “joked” about burning her house.

Matthew Perpetua: Pop stans maybe take Pitchfork’s judgment more seriously than most anyone else does, probably because they’re so eager to have the stuff they like validated.

Mapes: The women who were reviewing pop records, they talked. People were afraid. They understood the power of stan groups.

Zhang: If someone was writing a controversial review, they would be told, “Hey, let us know if your mentions get out of hand,” and maybe they would advise us to deactivate. It felt very much like Pitchfork staff trying to look out for freelancers and each other. It didn’t really feel like Condé was concerned about these types of things.

Mapes: It still gives me anxiety. There’s all this big pop stuff coming out, and I feel like I should pitch reviews, but I don’t want to because I don’t want to engage with that. And also, I don’t know who it serves, because everyone knows these things are coming out. It’s not shining a light on artists. It’s not necessary. It’s not like a smaller artist or even a mid-level artist that you’re making a case for.

Moreland: In bargaining, we would always say something like, “What if Condé just decides it’s not interested in Pitchfork anymore?” Condé would be like, “Oh, that would never happen.” That’s basically exactly what happened.

—“Condé Nast Is Folding Pitchfork Into GQ, With Layoffs,” New York Times, Jan. 17, 2024“Both Pitchfork and GQ have unique and valuable ways that they approach music journalism,” Ms. Wintour said, “and we are excited for the new possibilities together. With these organizational changes, some of our Pitchfork colleagues will be leaving the company today.”

Mapes: This was a complete blindside—like, 15 minutes before a mandatory all-hands Zoom with Anna Wintour. Puja’s not invited. She doesn’t know about it. Anna starts speaking about the GQ thing and how some of our colleagues will be departing today, but in extremely vague terms. People even internally thought the site was being shut down.

Moreland: Big artists reached out to a lot of my laid-off co-workers to say thank you. Artists who had been criticized by these writers being like, “I always enjoyed your writing.” Artists read Pitchfork, and that was always cool, too.

Dan Le Sac: Ticket sales went up. Pitchfork drove more listeners to us with that 0.2 than it would have if they’d just given us a vicious 5.

Drake: A lot of the people on the label side, who I respect and know, actually root for a very strong critical apparatus. In a spiritual sense, there’s more support for a strong music press than one would think when talking about the guys that keep cutting these jobs and destroying these publications.

Schreiber: The site’s still operating with 8.5 million unique monthly visitors and 3 million Twitter followers. They’re obviously doing something right.

Adam Krefman: That’s kind of all you can ask of an editorial team at a website—that’s the metric. So even if Condé didn’t understand Pitchfork, they could understand that the numbers were strong.

“I Guess It Wasn’t Enough” (Epilogue)

Matthew Perpetua: I think to some extent what people are mourning with Pitchfork is music publications having that kind of power at all.

Scott Plagenhoef: I think we proved that you could reach an audience by first and foremost taking that audience, and the music, seriously. I think we proved that leading with quality—long reviews, no photo books, no comments—had a home.

Adam Krefman: How many times have you read a Pitchfork review and had seven tabs open at the end of it so you could figure out what all these references are? And then you’re down a wormhole and you found three other things? It’s the discourse and the context, all with the discovery. I think that’s what everyone’s mourning.

Jayson Greene: Streaming certainly ate into the market value of what it meant to be a curator, because the minute you give someone who is funding the engines a whiff of the idea that an app can do this thing that they think they need people to do, then they will stop spending money on the people and they will start spending on the app. That is time immemorial.

Mark Richardson: Once all music became accessible, music criticism was really for people that like to read music criticism. It’s not for the general public anymore, and I don’t think it ever will be again.

Tom Breihan: I don’t think it has anything to do with the audience for this stuff. I don’t think it has anything to do with the buzziness or the culture surrounding the site itself. I think it is just these money people coming in and making bad decisions. If they’re going to lay off people in Boeing and cut safety protocols or whatever, they’ll do it to anyone. And they did it to Pitchfork.

Carl Wilson: It seems possible to me that the only thing that is going to survive of Pitchfork is album reviews, and that everything else they do is going to disappear. They’ll just be the album review vertical of GQ.

Will Welch (global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork): This is the beginning of a new era at Pitchfork. We are thinking big about what role music criticism and journalism should play in the era of recommendation algorithms. How can Pitchfork continue to serve music fans in ways that the machines cannot? With such a large, loyal readership, and so few other media outlets operating in the daily music space, the opportunity is huge and exciting.

Ryan Schreiber: I think people are premature to eulogize Pitchfork, because there are still a handful of people there who are continuing its mission, albeit with a skeleton crew of a staff. I have been very pleased at the job that Jeremy Larson and Matthew Strauss and the others have been doing in this sort of interim period. To me, the question is, Well, what happens whenever whoever they hire for the next editor in chief gets in that role?

Wilson: A couple of weeks ago in Toronto, I ran into an artist who had been the subject of some major indie attention. It was a wintry night, and I had just come from a friend’s birthday party, and he was just hanging around outside. I said, “It’s been a rough week with Pitchfork and everything.” And he said, “Oh, really? Because I feel like Margaret Thatcher just died.”

Timmhotep Aku: I think people have to hold the contradiction that Pitchfork provided a lot of opportunity for people to have careers in writing across the board who may not have otherwise gotten the chance. But I also think that Pitchfork has a legacy of not being self-interrogating, in a very white way.

Brian Howe: It only seems like this big monolith because it became so important somehow. But otherwise, it’s a lot of individuals, maybe strange people, working really hard to do a thing that’s strange and futile, in a way.

Greene: It was always, and only ever, a bunch of nerds writing essays about records. It was that before it became famous. And it was that after it became famous. It was only ever that, and those are the people who still come to Pitchfork, but I guess it wasn’t enough.

Amy Phillips: I think we had our time, and we were lucky that it was a very long time.

Perpetua: I think, broadly, I would say I don’t think we need to maintain Pitchfork. I think we can kind of see this as a sort of death.

Zola Jesus: Making music is a lonelier process now. I can make one of the best records of my career in 2024, and I put it out, and less people than ever will hear it, not only because there’s no more music journalism but because people don’t even know about it because of the algorithms. It kind of feels like shouting into a void.

Andrew Nosnitsky: Maybe just let Pitchfork go away and see what cool hobbyist blogs emerge in its wake. We can start the whole horrible cycle over again and see which of those blogs become the institutions over the course of 20 years, if ever.

Megan Jasper: I do think the one thing that I’ve learned over time is that when there is a vacuum—and there is one now—something else comes up.

Aku: If you’re going to do something better, it has to be different. “I’m going to be Pitchfork but brown” or “I’m going to be Noisey but Black” is corny to me.

Perpetua: You could imagine a future where Ryan Schreiber eventually buys Pitchfork back. I don’t think he necessarily should, but it’s his baby, and I would not blink at it.

David Drake: The impact of something like Pitchfork is just not what it once was, with things going to TikTok and YouTube. But those things are all also on a timer, the same way that Pitchfork was. Part of me wonders if all this is a lesson in impermanence.

Quinn Moreland: The world is so cruel right now on so many levels, and the cultural sphere is a reflection of that.

Jeff Weiss: I think it was easy to hate on Pitchfork. And probably some of it, at the time, was deserved. But find me anyone who’s confident in their taste and their opinions that isn’t worth being hated on at any moment.

Chris Kaskie: You’d rather have 10,000 people caring a lot about you than a million people who don’t give a shit.

Update, March 19, 2024: This article has been updated to clarify when Mark Richardson first contributed to Pitchfork.